FOR a brief moment, it looked like there was a chink of light for the Government.

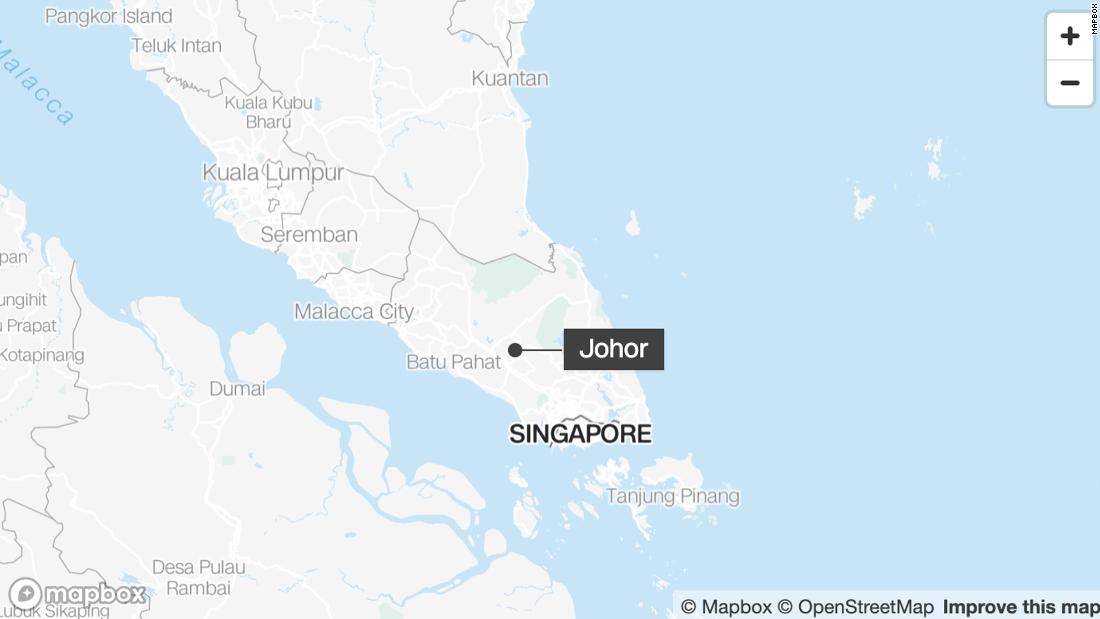

With Donald Trump decreeing trade policies on a whim via social media, the UK looked like it might be a safer bet than the rest of Europe when it came to threats of tariffs.

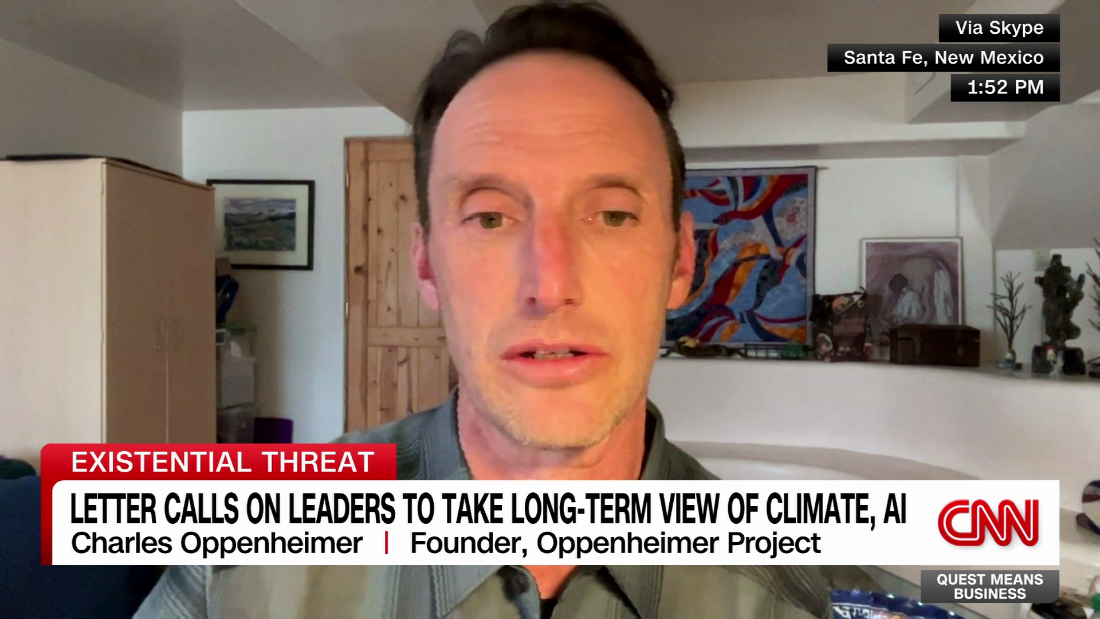

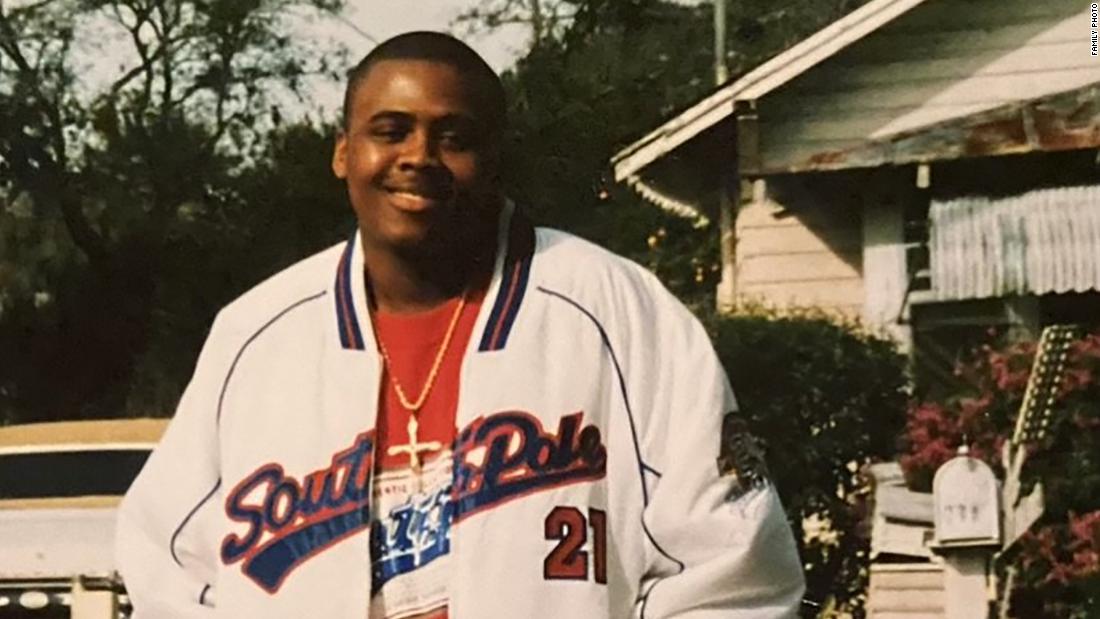

AFPRachel Reeves says getting more money into people’s pockets remains her ‘number one mission’[/caption]

But that’s hard to square when inflation is shooting up far higher than had been expected

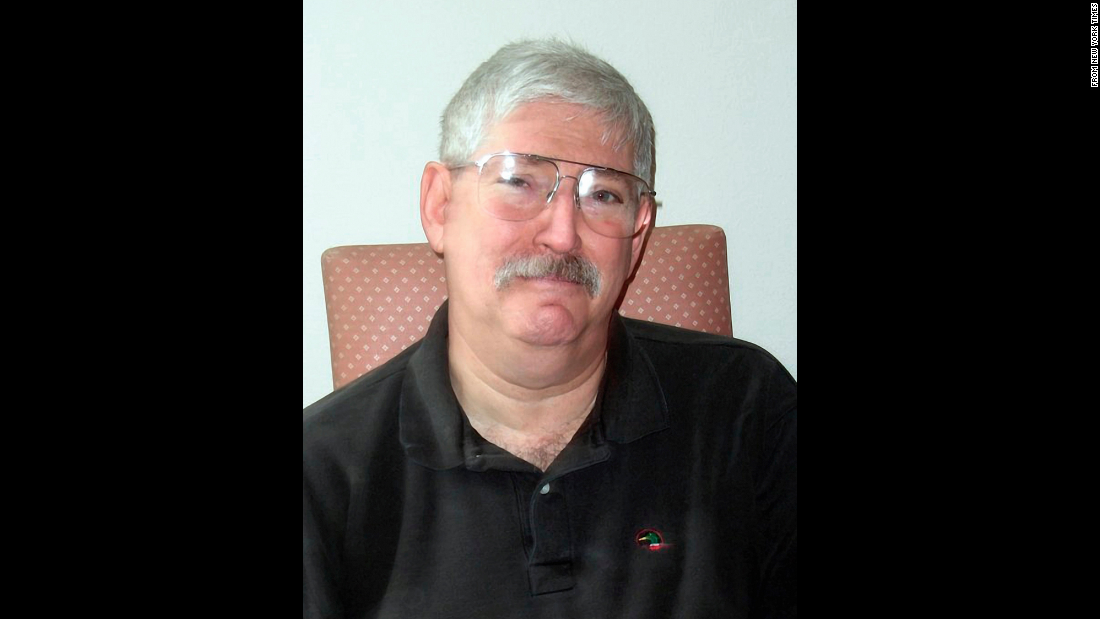

GettyA sharp rise in food and drink prices was one of the key inflation drivers[/caption]

But the UK’s attractiveness rapidly diminishes as soon as investors take a look under the bonnet.

What’s very problematic for Chancellor Rachel Reeves is that blame for the latest rise in inflation is landing squarely in Downing Street.

She was yesterday quick to say getting more money into people’s pockets remains her “number one mission”.

But that’s hard to square when inflation — seen as the biggest enemy when it comes to how people feel about their finances — is shooting up far higher than had been expected.

Out of reach

Official figures yesterday confirmed the rate of price rises has ticked back up to three per cent.

That’s a big jump on the 2.5 per cent announced last month and higher than the 2.8 per cent economists had predicted.

The biggest drivers have been, according to the Office for National Statistics, higher airfares and energy costs, a sharp rise in food and drink prices and the VAT tax charge on private schools.

Meanwhile, renters are suffering even higher monthly costs and people’s chances of ever owning their own homes have become further out of reach because of increased mortgage costs.

Already, traders were yesterday backtracking on bets the Bank of England will be able to cut interest rates again soon.

After previously being widely attacked for not having acted quickly enough to tackle inflation, the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street will undoubtedly be cautious about allowing increasing inflation to rear its ugly head again.

Ms Reeves yesterday was quick to say wages are rising at their fastest rate in three years, reasoning that people were therefore better off and able to afford these prices.

But wage growth might actually dampen the chances of further interest rate cuts from the Bank — which meets next month then again in May — because it is so worried higher earnings will make it easier for companies to push through price increases.

Higher wages, higher interest rates and higher prices would be easier to stomach if the economy was growing.

But it’s not. Latest figures showed the UK narrowly avoided recession, with a meagre 0.1 per cent growth.

As the Tories point out, when official figures look at how the UK economy has performed per person (GDP per capita) there has been a technical recession.

So, instead, we are now staring down the barrel of close to zero growth, higher prices and higher interest rates.

GettyConsumer spending is already starting to weaken[/caption]

APWith Donald Trump decreeing trade policies on a whim, the UK looked like it might be a safer bet than Europe when it came to tariffs[/caption]

It’s no wonder that “stagflation” headlines will start to follow Ms Reeves like a nasty smell.

Several weeks ago, I was in the audience in Oxfordshire when the Chancellor delivered her big, optimistic growth speech. She managed at least 31 mentions of the word “growth” in the space of 40 minutes.

But this isn’t the Land of Oz — and chanting the word will not make it miraculously happen.

So far, Labour’s big promise of growth rests on a lot of projects in faraway lands. There’s the rehashed ideas for Heathrow’s third runway, and plans for overdue spending on reservoirs and much-needed homes.

Business confidence has been shattered

Meanwhile, the great green energy transition will do little for household bills in the short term as we remain landed with the world’s highest electricity costs.

The Government needs to realise it can talk about “taking on the blockers” to growth until it’s blue in the face — but it means absolutely nothing to ordinary people unless they are brought along on the journey.

At the moment, there is little for households or firms to feel chipper about.

Business confidence has been shattered by the Budget’s tax raid and consumer spending is already starting to weaken as workers worry that companies will soon follow through with their warnings about job cuts.

The Government needs to remember the UK’s economy is as much a confidence trick as it is about policy.

Some of the biggest retailers, including Morrisons, Next and Marks & Spencer have called on the Chancellor to relieve some of the pain she has unleashed, by staggering the looming National Insurance changes in April.

But Treasury sources tell me that isn’t going to happen — businesses will have to stomach it. That realisation is already happening in some big boardrooms.

Their top brass also worry that if they continue abusing the Government about not understanding business, the rest of the world will believe them.

That will mean international investors will start to view the UK as a basket case again and there will be an even bigger sell-off of UK PLC.

One chief executive of a FTSE 100 company told me recently that it was in their interest for this Government to succeed — if only for the sake of their share price.

The Government needs to remember the UK’s economy is as much a confidence trick as it is about policy.

It should stop with the falsehoods about helping people’s pockets when not a single person believes them.

Why does inflation matter?

INFLATION is a measure of the cost of living. It looks at how much the price of goods, such as food or televisions, and services, such as haircuts or train tickets, has changed over time.

Usually people measure inflation by comparing the cost of things today with how much they cost a year ago. The average increase in prices is known as the inflation rate.

The government sets an inflation target of 2%.

If inflation is too high or it moves around a lot, the Bank of England says it is hard for businesses to set the right prices and for people to plan their spending.

High inflation rates also means people are having to spend more, while savings are likely to be eroded as the cost of goods is more than the interest we’re earning.

Low inflation, on the other hand, means lower prices and a greater likelihood of interest rates on savings beating the inflation rate.

But if inflation is too low some people may put off spending because they expect prices to fall. And if everybody reduced their spending then companies could fail and people might lose their jobs.

See our UK inflation guide and our Is low inflation good? guide for more information.

Published: [#item_custom_pubDate]