IT WAS one of English football’s bleakest nights and one of its most significant occasions.

The Kenilworth Road riot — before, during and after an FA Cup quarter- final between Luton Town and Millwall on March 13, 1985 — was a hideous orgy of disorder which had profound ramifications for the English game.

PAThe 1985 Luton riot occurred before, during and after a 1984–85 FA Cup game[/caption]

GettyFans stormed the pitch after Luton beat Millwall 1-0[/caption]

AlamyIt was halted by Millwall fans for 25 minutes and ended with a frightening riot[/caption]

GettySeats in Kenilworth Road were destroyed[/caption]

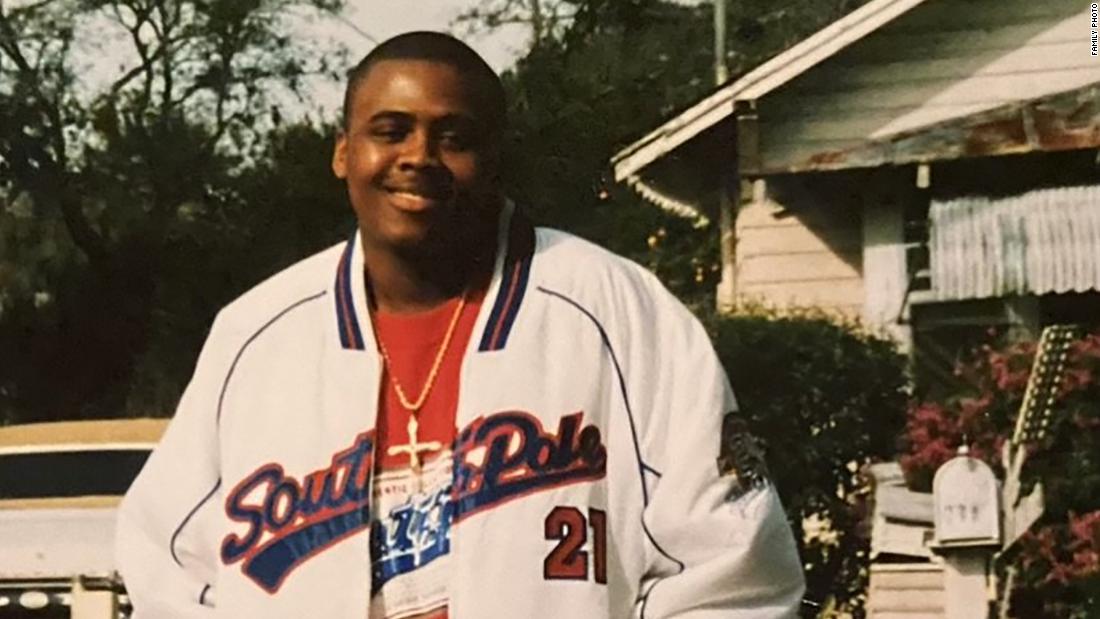

Former Luton gaffer David Pleat spoke exclusively to SunSportRex

Forty years ago today, Millwall’s infamous Bushwackers firm were joined by a band of ‘freelance hooligans’ from Chelsea and West Ham.

Luton’s home ground became dangerously overcrowded, sparking a series of violent pitch invasions as an entire town was turned into a war zone.

Eighty-one people were injured, including a policeman who had to be resuscitated after being knocked out by a concrete slab.

A knife was thrown at Luton keeper Les Sealey. Hundreds of seats were ripped out and used as missiles.

Billiard balls were hurled into the directors’ box, before a pitched battle raged between hooligans and police.

David Pleat, who managed Luton that night and for 12 years over two spells, told me: “The victims of the violence — many of them either very young or old — were treated in the players’ tunnel. There was blood everywhere. The scenes were horrific.”

“Outside, homes, pubs and shops were vandalised. Carriages on a train carrying travelling fans had ceilings torn out and, according to police, were left “looking as if a bomb had gone off”.

In that spring of 1985, English football was entering its lowest depths.

Cheltenham Festival betting offers and free bets

The Luton riot would be swiftly followed by the Bradford City fire, in which 56 supporters perished, and the Heysel disaster at the European Cup final in Brussels, when rioting by Liverpool fans and a crumbling stadium caused the deaths of 39 people — mainly supporters of Juventus.

As a result, English clubs would be banned from all European competitions for five years.

AlamyPoliceman and dogs were deployed onto the pitch[/caption]

AlamyPolice with batons out tackled fans invading the turf in 1985[/caption]

GettyThen manager Pleat has included details in his new autobiography[/caption]

For many years before, football supporters had been treated like animals and far too many acted accordingly.

Pleat recalls that Margaret Thatcher’s government was already “waging war” against the battered national sport, scapegoating football for society’s ills.

And after the Kenilworth Road riot, Thatcher found a willing ally in Luton chairman David Evans.

The soon-to-be Tory MP introduced a ban on away fans from his club’s stadium, as well as an ID card scheme which the prime minister sought to have introduced for supporters nationwide.

It was only after the horrors of the 1989 Hillsborough disaster — and the subsequent Taylor Report which deemed the scheme unworkable — that the national ID card project was abandoned.

Anyone who watched football from behind fences in the 1980s would have experienced dangerous overcrowding and been in little doubt that the deaths of 97 Liverpool supporters at Hillsborough could have happened to fans of any club.

After Lord Chief Justice Taylor’s intervention, all-seater stadia were made compulsory in the top two tiers of English football.

Along with the advent of the Premier League, the game and its venues would be transformed.

GettyPolice and fans battled during Luton vs Millwall[/caption]

AlamyThe aftermath of the riots brought huge changes in English football[/caption]

Luton’s away-fan ban ran from 1987 until 1991. Many clubs banned Hatters supporters in a tit-for-tat.

And Luton were thrown out of the League Cup for one season after refusing to back down.

Football supporters were societal pariahs in the 80s. And Luton — the riot’s victims — would become hated inside the sport.

Pleat damningly describes the late Evans as “a visionary in his own mind” and “a lapdog for Mrs Thatcher”.

He added: “Evans was not a good person and Luton became widely hated because of his actions.”

On the 40th anniversary of the riot, the details sound difficult to comprehend.

The match was not all-ticket, although matches very rarely were.

The trouble was premeditated and organised, yet police were unprepared — despite the sight of thousands of known hooligans congregating at London’s St Pancras Station four hours before kick-off.

Bedfordshire’s force had no horses, with reinforcements arriving from Cambridgeshire only after serious disorder had flared.

Soon-to-be Tory MP David Evans was the chairman of Luton Town at the timeRex

GettyAway fans were banned from Kenilworth Road from 1987 until 1991[/caption]

Stadium overcrowding was a huge problem in the 80sRex

The overcrowding was dangerous and, in Pleat’s words, the arrangements were “completely chaotic”.

But the English domestic game, now the envy of the world, was unrecognisable four decades ago.

Conditions at most stadiums were appalling, violence was rife, overcrowded terraces endangered lives, fans were herded like sheep, barked at by police dogs, and watched matches from behind barbed-wire fences or within cages.

David Brown, a 59-year-old Hatters supporter who attended the Millwall match as a teenager, said: “You would go to away matches in those days and be terrified.

“I remember going to Newcastle in the 80s and being scared to open my mouth for fear of being beaten up.

“Last season I went to St James’ Park for a 4-4 draw and Newcastle fans couldn’t have been friendlier.

“When you think of the conditions you’d watch football in back then, you wonder why we bothered going.

“I’d seen other serious outbreaks of hooliganism — but nothing like the Millwall riot.”

GettyStewards were asked to clean up Luton’s ground the day after the riot[/caption]

Those who complain about the ‘sanitisation’ of the modern match-going experience tend to conveniently forget how bad things were in the ‘good old days’ of the 70s and 80s.

English football was a powder keg. The Luton riot was the night it truly exploded.

The Kenilworth Road End, which was supposed to house travelling Millwall fans, became overcrowded as their numbers had been seriously swelled by supporters of rival London clubs.

Kick it upfield, I’ll blow the final whistle, then run for your life.

Referee told goalkeeper Sealey

Brown later worked with a Chelsea fan who had been at the Kenilworth Road riot and admitted to becoming a ‘freelance hooligan’ because “we all wanted to have a go at Luton”, whose own hooligan fringe had been involved in violence at grounds in the capital.

By 7pm — 45 minutes before kick-off — a gate had been forced open, leading to crushing, with hundreds of fans invading the pitch and goading Luton supporters in the opposite Oak Road End of the ground.

Remarkably, the game kicked off on time but after 14 minutes there was a further pitch invasion, which led to a 35-minute delay.

Soon after, forward Brian Stein scored the only goal of the tie for top-flight strugglers Luton against Millwall’s Third Division promotion chasers, with Pleat admitting “we all feared the worst”.

PALuton Town executives John Smith and Millwall chief executive Tony Shaw met with Sports Minister Neil MacFarlane to discuss the violent clashes in 1985[/caption]

But referee David Hutchinson, a policeman himself, was determined to finish the match.

Just before the end, with Sealey about to take a goal-kick, Hutchinson told Sealey: “Kick it upfield, I’ll blow the final whistle, then run for your life.”

And all 22 players sprinted for the relative safety of the dressing rooms.

For Pleat, reaching an FA Cup semi-final should have been a career highlight.

Instead, that achievement was utterly tarnished.

The next day he was dragged into an emergency meeting in Parliament — with Luton’s bosses, as well as FA chiefs, grilled and urged to get their house in order.

Yet Millwall would be fined a measly £7,500 — a punishment overturned on appeal.

Kenilworth Road had been trashed and Evans used the opportunity to ban away fans, to build several executive boxes on the site of the vandalised Bobbers Stand, to install a controversial plastic pitch, as well as introducing the away-fan ban and ID card scheme.

PAMillwall boss George Graham led his players off and later told Pleat he wanted to leave the South London club[/caption]

Brown said: “Evans used the trouble for his own political means. He gave a rabble-rousing speech at the next Tory party conference and, at the next election, he was elected an MP.

“The away-fan ban made Luton very unpopular — but the hypocrisy of Evans was that wealthy away fans who could afford the executive boxes were still welcome.”

Millwall’s manager that night was George Graham, a friend of Pleat’s ever since they had faced each other in an England v Scotland schoolboy international in 1960, through to their time as rival managers of Tottenham and Arsenal, to the current day, with both men now aged 80.

Pleat said: “Before kick-off, George used the stadium’s loudspeaker to urge the Millwall fans to get off the pitch.

“We were the last two people inside Kenilworth Road that night and George then told me he wanted to leave Millwall.

“They won promotion that season but the following year he was off to Arsenal.”

Pleat claimed: “A third of Luton season-ticket holders stopped going to matches after the riot, never to come back.”

Thirty-one people were arrested for the violence, appearing at Luton Magistrates Court the next morning.

But with Hatters fans waiting outside, at least one Millwall supporter — who had been fined, then freed, for his part in the riot — lost his bravado and refused to leave the courthouse for fear of reprisals.

Pleat said: “People forget how dark a place English football was in back then.

“The Bradford and Heysel disasters would come soon after.

“Now supporters can enjoy matches in decent conditions — but back then, it was a very different game.”

Just One More Goal — The Autobiography of David Pleat is available from Biteback Publishing.

Creator – [#item_custom_dc:creator]