IT is a journalist’s job to p**s people off – so when Russia put me on a wanted list, I knew I had done something right.

The Kremlin was trying to scare me, to stop me and my colleagues doing our jobs. But it has had the opposite effect.

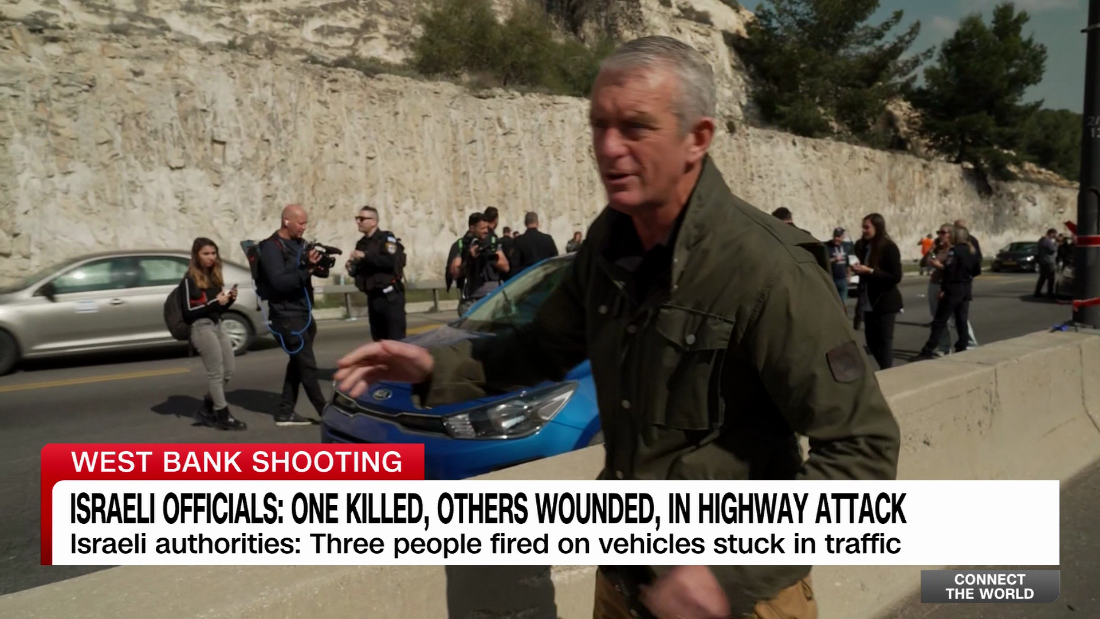

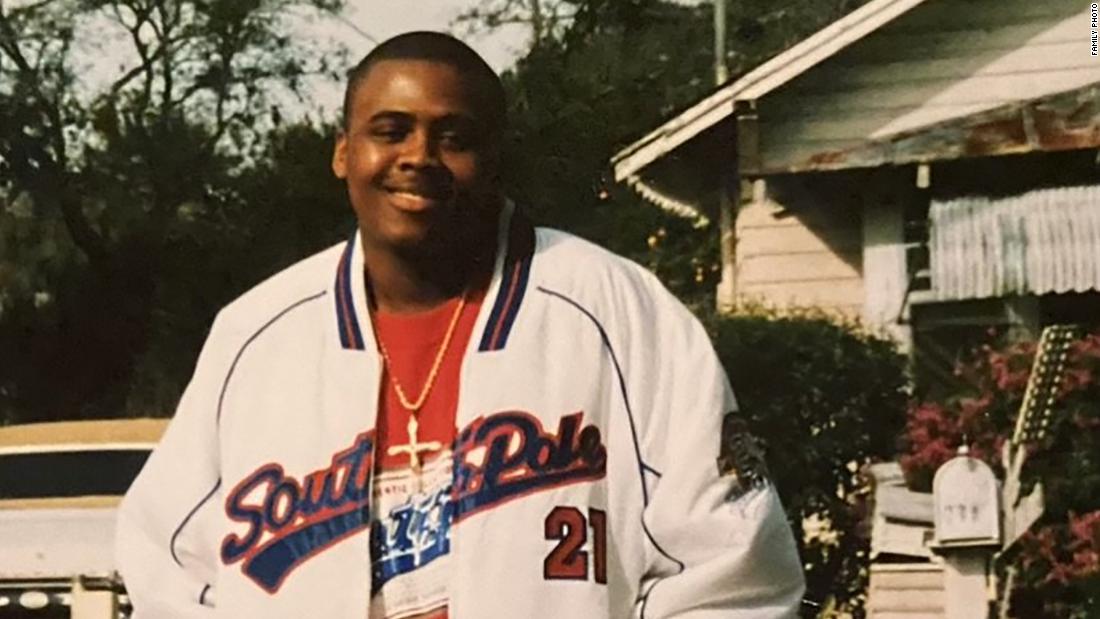

Ian WhittakerAward-winning journalist Jerome Starkey pictured in front of a damaged building in the main square in Kursk, Ukraine[/caption]

Volodymyr Zelensky exclusively spoke to Jerome in November 2023

GettyJerome has vowed to not cower to Putin’s threats[/caption]

In the days since a Russian court detained me “in absentia”, The Sun has doubled down on its fearless frontline reporting.

Our Foreign Editor Nick Parker filed two superb dispatches revealing the awful human cost of Vladimir Putin’s slaughter.

When I found out last week, via Twitter, that the Leninsky District Court in Kursk had put me on an international wanted list I joked: “It’s always nice to feel wanted.”

But I won’t lie to you – it is also unnerving.

The mind races to Russian murders and chemical weapons attacks in Britain.

There was the radioactive Polonium slipped into a defector’s tea in 2006 and the deadly Novichok nerve agent sprayed on a Salisbury door handle in 2018.

Friends suggest, in moments of dark humour, that I stay away from balconies or move into a bungalow as so many Kremlin critics fall mysteriously to their deaths.

When I appeared on Good Morning Britain, Susanna Reid and Ed Balls asked what extra steps to stay safe was I taking.

I think of my family. Then I take a deep breath.

Putin has much bigger problems than the Defence Editor of The Sun. Surely.

Moscow’s foreign death squads track down oligarchs and turncoats. Not journalists.

Our American colleague Evan Gershkovich was detained for 16 months on trumped-up spying charges.

Then I remember Anna Politkovskaya, shot in her Moscow apartment block in 2006. And the British cameraman Roddy Scott killed by Russian troops in 2003, as he covered the second Chechen War.

The fact remains that the greatest threat to my life is indiscriminate Russian shelling on my many reporting trips to Ukraine.

In Kharkiv, I hid by a municipal flowerpot as a barrage of Grad rockets rained down all around us – and in front of me a hero Red Cross medic continued to treat a wounded civilian who had been cut down by an earlier blitz.

I was blown out of bed in Kramatorsk as a volley of missiles ripped 50 foot craters in the grounds of a neighbouring school.

I have almost lost track of the hotels I have stayed in which have since been levelled in Ukraine. Last Friday it was the Bristol, an iconic landmark in Odesa.

And that reminds me why we do this work.

Jerome, far right, hides behind a flower pot as a Red Cross medic continued working in Kharkiv, 2022

APReporter Evan Gershkovich following his release as part of a 24-person prisoner swap between Russia and the US in August 2024[/caption]

Ex-Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia were poisoned by nerve agent Novichok in Salisbury in 2018Rex

News Group Newspapers LtdForensic teams in hazmat suits working where the father and daughter were found[/caption]

I can come and go from Ukraine. But millions of innocent people –men, women and children – are enduring this war’s horrors every single day.

Families are ripped apart. Limbs and lives are lost, too many to keep count.

We try to tell those people’s stories to help you understand what is unfolding on our doorstep. And if telling the truth upsets Moscow, so be it.

I am used to upsetting governments. I was thrown out of Kenya in 2016 when I was the Africa Correspondent for The Times. Sadly Nairobi has never said why.

In 2010, I went head-to-head with Nato in Afghanistan. I exposed a gruesome cover-up of civilian casualties by US Special Forces.

That taught me an important lesson. When someone tries to stop you reporting, you have to carry on.

Nato accused me of lying. They said my account of the mission in Khataba, in eastern Paktia province, was “categorically false”. I plugged on. There was evidence in my notebook.

I had been to the scene. I knew the men who were killed were not Taliban. One was a policeman. One was a local prosecutor.

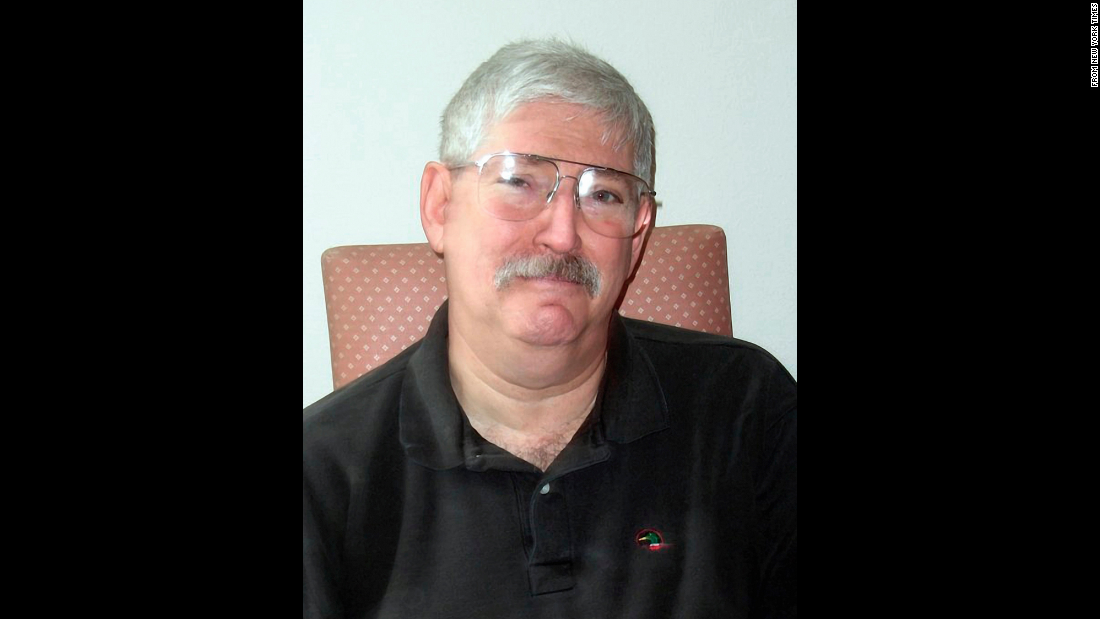

Peter JordanJerome joined soldiers of the 3rd Assault Brigade of the Ukrainian army in the suburbs of Bakhmut in Ukraine in 2023[/caption]

Peter JordanJerome pictured in the outskirts of Odesa after a Red Cross depot was hit by a Russian missile attack[/caption]

The two pregnant women weren’t insurgents. Nor was the teenage girl, cut down in a hail of bullets.

Eventually Nato backed down. Vice Admiral William McRaven, the commander of America’s Joint Special Operations Command who later led the Osama bin Laden mission, visited the survivors to apologise.

His visit was one the most extraordinary scenes I have ever witnessed. McRaven – author of the bestselling book Make Your Bed – offered to sacrifice a sheep at the family’s door, in an ancient local ritual to seek forgiveness.

Those stories didn’t change the tide of history, or even the course of the war in Afghanistan.

But it showed that journalism makes a difference. An injustice was exposed and acknowledged, and in some small way redressed. It made a difference for that family.

And if our reporting from Ukraine can make it better for one family, then that will makes our job worthwhile. I don’t care how much it pains the Kremlin.

If Russia wants me or The Sun to stop reporting on the war in Ukraine, the only way is to end the war. It has gone on for three years too long.

Published: [#item_custom_pubDate]