AGED 21, Joanne Mackel walked into Northumbria Police Station on her first day as an officer recruit.

Her reason for joining was simple: She wanted to find out the truth about what happened to her mum, Ann Law, who had disappeared in 1973 when Joanne was just five.

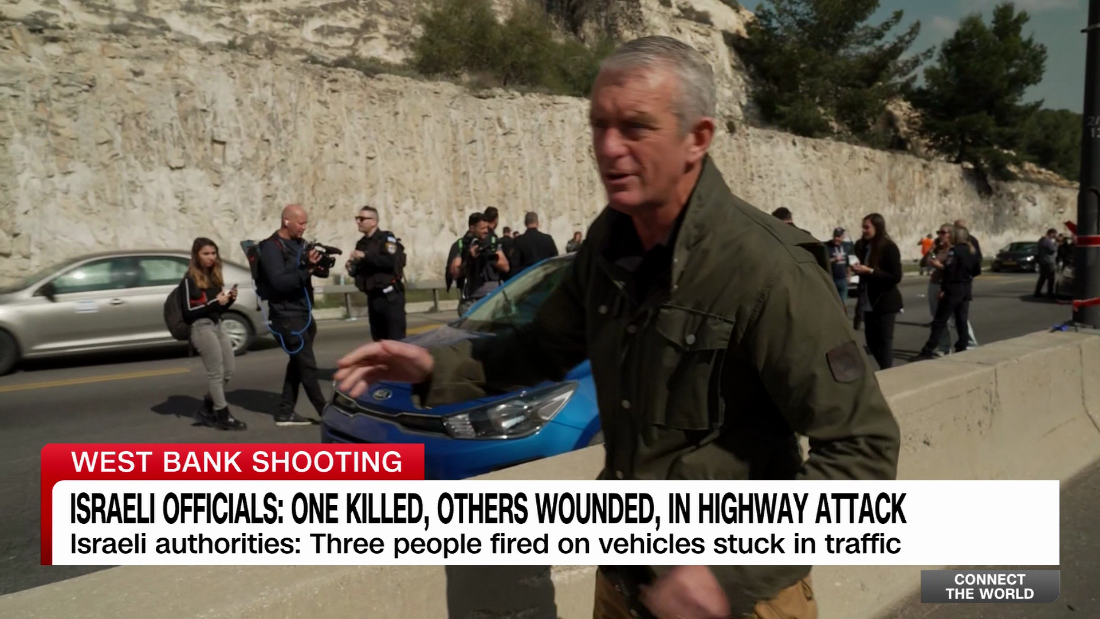

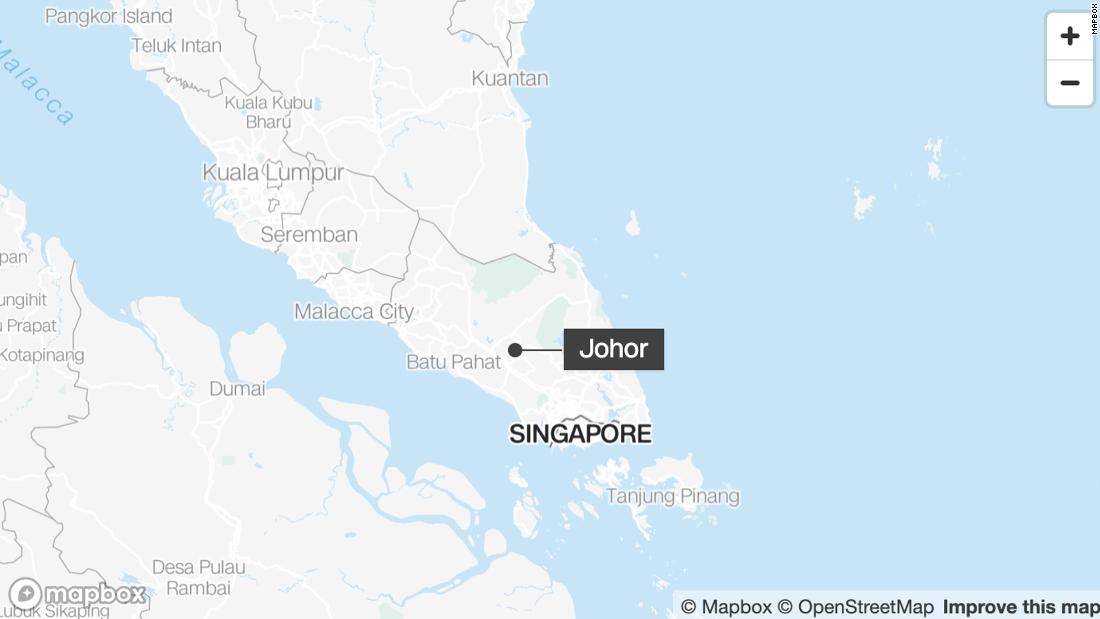

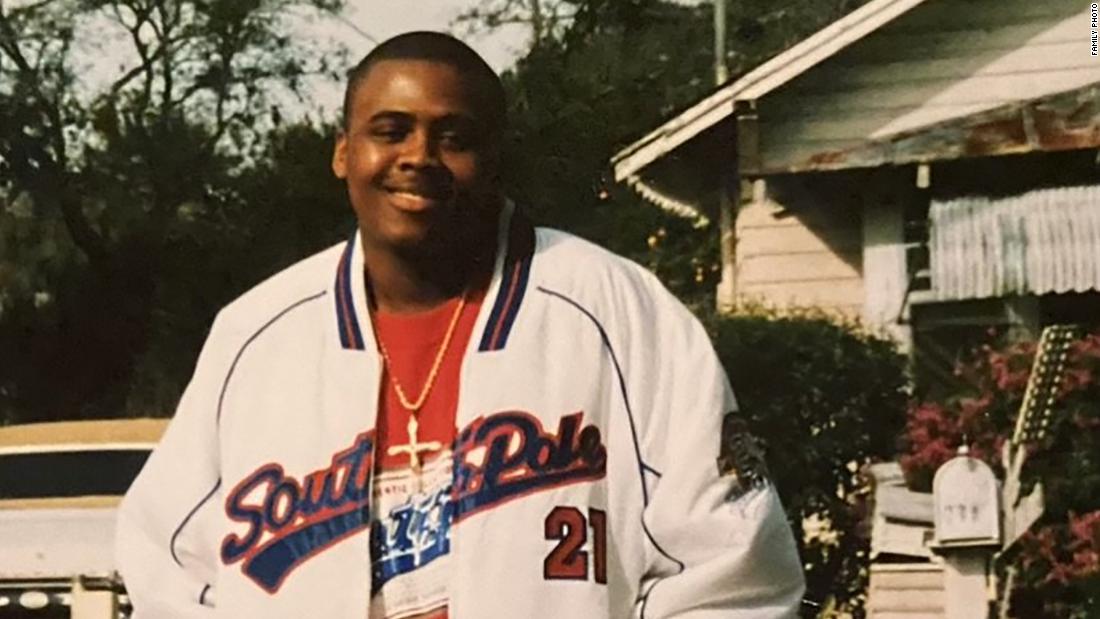

Joanne on the banks of River Tyne, where her mum Ann Law’s body is believed to have been hiddenSupplied

Joanne’s dad had already twice tried to kill Ann, pictured, and the children — once by cutting the car brakes and another time by leaving the gas onSupplied

SuppliedJoanne’s dad Gilbert with her mum Ann and her brother Trevor as a baby[/caption]

The trainee cop also wanted answers about what she believed was a bungled police investigation.

In 1983, ten years after Ann was last seen alive, Joanne’s dad, Gilbert Law, was charged with her murder — after he had asked his son Trevor to help “dig up your mam”.

The case was eventually abandoned, but Joanne, who served in the police under her mother’s maiden name, Wallace, was convinced he had done it.

“I was only five years old when my mam disappeared,” she tells me, when we meet at her stylish home near Morpeth, Northumberland.

“I’m 57 now, and I’m determined to hold the police to account for what I believe are catastrophic failures in the investigation.

“Had it been handled properly, I might not have spent 50 years wondering where my mam is buried.”

I first met Joanne in summer 2023, when she contacted me to ask if I would help investigate what happened to her mother.

The outcome is a six-part podcast series on the case, launched to mark the 52nd anniversary of Ann Law’s disappearance.

Joanne has the steel of a seasoned detective, reminiscent of Helen Mirren’s DCI Jane Tennison in Prime Suspect. Equally sharp and unflinching, she is the kind who could stare you down in an interview room.

She is also as glamorous as Tennison, her blonde hair carefully styled and her make-up perfect.

“It must be genetic,” she says with a smile. “My mam would never leave the house without lippy on.”

In 1973, Joanne’s family consisted of her nine-year-old brother Trevor, her father Gilbert [a merchant seaman] and her mother Ann, 34, to whom the children were devoted.

Out of control

Ann was an identical twin, and very close to her sister Margaret.

Recalling the tragic day when she last saw her mother, Joanne says:

“We went to bed on a Saturday night and a few hours later there was loud banging and the sound of Mam screaming, so Trevor went downstairs.”

What her terrified brother told Joanne did not make sense to a five-year-old.

She continues: “He said that he had seen Mam lying by the fireplace, not moving, and Dad was sitting in his chair, staring at her.”

The next day, when Ann did not show up for a planned outing, her sister Margaret came to the house.

“I was upstairs looking out of the window from my bedroom, and I could hear her shouting at my dad,” says Joanne.

In the late 1960s, Gilbert had been diagnosed with paranoid schizo- phrenia, and his medical records immediately prior to Ann’s disappearance show that he was spiralling out of control.

He had already twice tried to kill Ann and the children — once by cutting the car brakes and another time by leaving the gas on.

“He should have been locked away for the safety of his family and others,” says Joanne.

“Things would have been so different now if someone in authority had acted.”

Shortly before disappearing, Ann had separated from Gilbert, changing the locks and taking out a restraining order against him.

But Gilbert ignored it and bullied his way back into the family home.

“Police should have arrested him,” says Joanne. “But these were the days of Life On Mars [the BBC TV series that lays bare the casual sexism present in 1970s policing].

“And in those days, domestic violence wasn’t considered a crime.

“I saw him kick her to the ground, punch her in the face. I’ve seen her lying there in so much pain she couldn’t get up to come and get hold of me when I was crying after Dad stormed out.”

Aged 21, Joanne joined the police to find out the truth about what happened to her mum

SuppliedJoanne and her brother Trevor in the early Nineties[/caption]

SuppliedJoanne’s beloved brother Trevor went on to die of a heroin overdose in 2001, aged 34[/caption]

Ann’s disappear- ance was treated as a domestic or “voluntary missing person” situation.

“The police didn’t even search the house that morning,” she says.

“If they had, they would have seen she hadn’t taken any clothes, make-up, purse or passport. And, of course, she left us, her precious children, behind.”

Margaret reported her twin sister missing that same day. The following day, the first stage of Ann’s divorce papers came through — but police failed to make the connection.

Joanne said: “They insisted she had gone away to London, or shacked up with another fella, despite the fact she had only ever left the home to escape the violence.”

Because police only interviewed Gilbert as a witness — not as a suspect — he was free to board a merchant navy ship bound for the Caribbean, having made arrangements for his children to enter an orphanage.

Instead, they were placed in foster care with Christine and Thomas Hamill, where they were to suffer years of physical, sexual and psychological abuse.

I saw him kick her to the ground, punch her in the face. I’ve seen her lying there in so much pain she couldn’t get up to come and get hold of me when I was crying

By 1982, a 15-year-old Joanne was still living unhappily with the Hamills, trying to do well at school.

But Trevor, who had already left the house to escape the beatings, was unravelling. Then, something extraordinary happened.

Gilbert, who still insisted on sporadic contact with his children, took Trevor, then 18, and his cousin Stephen to the banks of the River Tyne at Bywell, between Hexham and Newcastle, after saying to Trevor:

“Do you want to come with me to dig up your mam?

“I’ll show you where your mam is. Do you want to come with us?”

The boys accompanied Gilbert to a local beauty spot — a place Ann had loved.

“We got out of the car, and he had a spade in each hand,” says Stephen, when I meet him at his home in Gretna Green on the Scottish border.

“The ground had already been disturbed, and I could see someone had been digging. Trevor started digging with his dad. I’m holding the torch and Trevor’s digging.”

Too grotesque

No body was found, but Gilbert was subsequently charged with Ann’s murder. This followed a confession that was obtained by his own son when police put Trevor in a cell with his father.

“Trevor didn’t recover from that experience,” says Joanne, tearful as she speaks about her beloved brother, who went on to die of peritonitis, brought on by heroin use, in 2001, aged 34 — the same age his mother was when she disappeared.

Gilbert was tried in November 1983, but the case was halted when he had a psychotic episode while giving evidence.

A second trial in June 1984 ended with the judge ordering a not guilty verdict on medical grounds, but directing the CPS to keep the case on file in case Gilbert was ever deemed fit to stand trial.

Joanne tried to get on with her life and threw herself into her role as a police officer. Then, in 1997, she came across Operation Rose, an investigation into child sexual abuse in children’s homes.

She says: “I was in one of the homes they were looking into, because I had been placed there having begged the social worker to get me out of the Hamills’ because of the abuse. I decided to tell my police colleague everything I knew, and the next thing, I’m at trial giving evidence against Thomas Hamill and his son, Martin.”

Christine Hamill was arrested for assault on Trevor, but the CPS would not authorise a charge.

Both men stood trial in 1999 and again in 2000. Thomas Hamill was acquitted due to CPS procedural mistakes, but Martin was convicted of indecent assault and unlawful sexual intercourse with a child under 13.

He was placed on the sex offenders register for ten years.

SuppliedSince the murder trial in 1983, little has happened in what has become Northumbria Police’s longest-running missing persons case (Ann pictured when she was around 18 years old)[/caption]

SuppliedJoanne retired from the police in 2017, having solved a number of rape cases and helped countless women escape domestic abuse[/caption]

Joanne says: “I will never forget standing there giving evidence at the trial. I was asked by the defence barrister, ‘You were very mature for your age — you had very large breasts, didn’t you?’.

“I couldn’t believe it, they were trying to blame me for being abused.”

Out of all her painful experiences, what hurts Joanne most is losing her brother.

She says: “He never stopped looking for Mam. When Fred and Rose West were arrested — 19 years after she went missing — Trevor went to their home and stood outside for hours, waiting to hear if she was one of their victims.”

Since the murder trial in 1983, little has happened in what has become Northumbria Police’s longest-running missing person case.

A cold case review led to another excavation at the same spot that Gilbert took Trevor and his cousin to dig.

He [Trevor] never stopped looking for Mam. When Fred and Rosemary West were arrested — 19 years after she went missing — Trevor went to their home and stood outside for hours

“In 2010, they found a human cheek bone,” Joanne tells me. “They asked for my DNA, and I said at that point, ‘For God’s sake, she’s got an identical twin sister, they have the same DNA’.”

In 2005, when her father was dying, police asked Joanne to wear a wire to see if she could coax a confession from him.

She refused, deciding it was too grotesque a thing to do. Joanne retired from the police in 2017, having solved a number of rape cases and helped countless women escape domestic abuse.

She has been commended for her exemplary policing on numerous occasions, but keeps the certificates in a box, not framed and hung on the walls.

“The one case I desperately wanted to solve was what had happened to my mam,” Joanne says.

“But I can comfort myself by knowing I have helped other women from meeting the same fate.”

The Dig Up Your Mam podcast is available at juliebindel.substack.com and on all major podcast platforms from Monday.

HOW YOU CAN GET HELP:

Women’s Aid has this advice for victims and their families

Always keep your phone nearby.

Get in touch with charities for help, including the Women’s Aid live chat helpline and services such as SupportLine.

If you are in danger, call 999.

Familiarise yourself with the Silent Solution, reporting abuse without speaking down the phone, instead dialing “55”.

Always keep some money on you, including change for a pay phone or bus fare.

If you suspect your partner is about to attack you, try to go to a lower-risk area of the house – for example, where there is a way out and access to a telephone.

Avoid the kitchen and garage, where there are likely to be knives or other weapons. Avoid rooms where you might become trapped, such as the bathroom, or where you might be shut into a cupboard or other small space.

If you are a victim of domestic abuse, SupportLine is open Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday from 6pm to 8pm on 01708 765200. The charity’s email support service is open weekdays and weekends during the crisis – [email protected].

Women’s Aid provides a live chat service – available weekdays from 8am-6pm and weekends 10am-6pm.

You can also call the freephone 24-hour National Domestic Abuse Helpline on 0808 2000 247.

Published: [#item_custom_pubDate]