POLICEMAN Norwell Roberts was walking down the street one bright summer’s day when a fellow cop wound down his car window and shouted “black c***!”

Norwell raced into nearby Bow Street police station in London‘s Covent Garden, where he was based, to report the incident to the Chief Superintendent but was told: “What do you want me to do?”

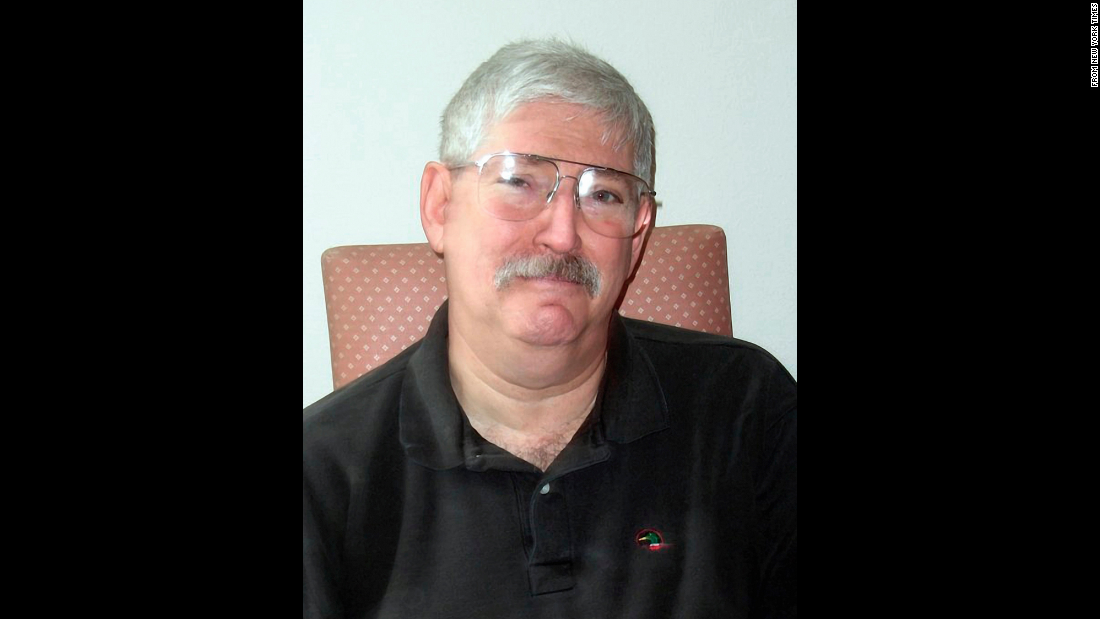

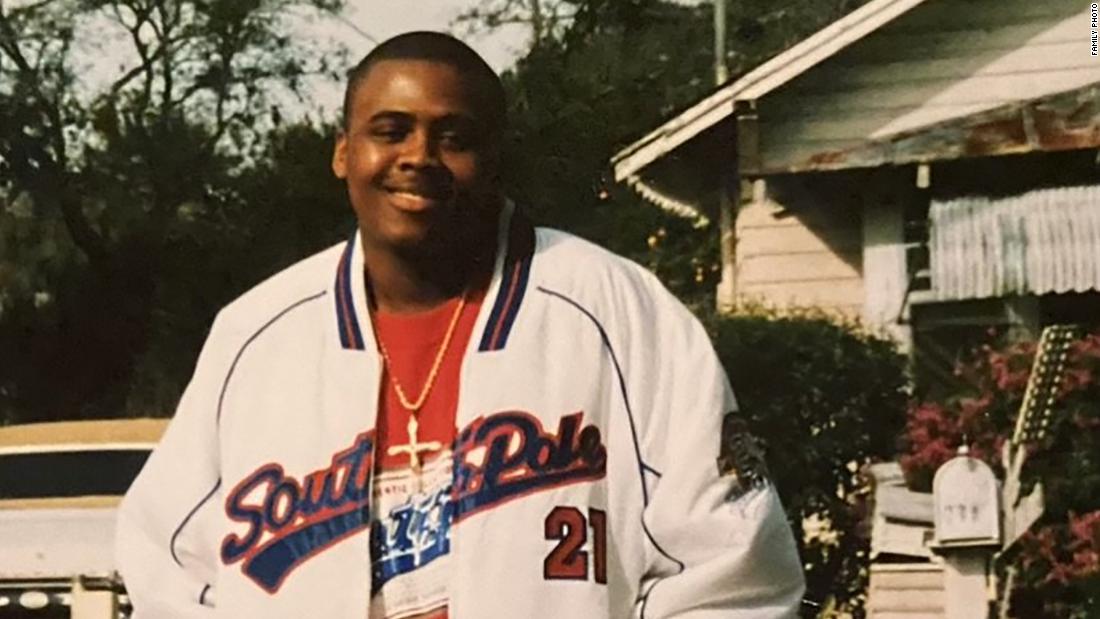

Norwell Roberts was the Met’s first ever black police officerNorwell Roberts

Norwell RobertsNorwell suffered horrific racism from his own colleagues[/caption]

Hulton Archive – GettyHe once had a chance meeting with gangster Ronnie Kray at the height of his notoriety[/caption]

“I thought f*** it, I let them get to me – that was the only time I showed it,” he said. “I went back to the station house, into the bath so no one could hear me and cried.”

Norwell, now 79, was the Met’s first ever black police officer, joining aged just 22 in 1967.

After answering an advert calling for more London cops, he found out he’d got the job when a pal showed him a headline in the Daily Telegraph stating: “London to have first coloured policeman soon.”

Norwell, speaking to The Sun from his home in Harrow, said: “I told him it can’t be me, I haven’t heard anything. But, of course, it was me.”

On my first day, my reporting sergeant said ‘look, you n*****, I’ll see to it you never pass your probation.’ I had the buttons ripped off my uniform, consistently called the n-word, cups of tea thrown at me, spat at – and that’s by the other policemen.

Norwell RobertsThe Met’s first black officer

After finishing training school he was stationed at Bow Street – now the home of the force’s Museum of Crime and Justice.

He recalls: “On my first day, my reporting sergeant said ‘look, you n*****, I’ll see to it you never pass your probation.’

“I had the buttons ripped off my uniform, consistently called the n-word, cups of tea thrown at me, spat at – and that’s by the other policemen,” he said laughing.

Walking the beat around Covent Garden, Norwell said the market porters became his friends – but not the cops.

“I’d have a joke and a laugh with people out and about, they made me feel welcome,” he said.

“The cockney porters would say ‘nice sun tan’ and I’d tell them ‘I’ve been to Southend’ and we laughed – it bridged the gap, I suppose.

“There was no humour from the policemen. The only thing they didn’t do was assault me.

“But when you’re spat at and swore at and made to feel unwelcome, that’s mental and can hurt more because they take a long time to heal if ever. If they hit me, I’d have a bruise but the bruise would go.”

Norwell said it was the first time he’d experienced “real racism“, adding: “I didn’t know anything about it.”

He’d moved to the UK from Anguilla in the Leeward Islands in the West Indies aged 10 to join to his mum, Georgina, who’d found work as a housemaid in Bromley, then part of Kent.

He remembered being told by his primary school’s head teacher he wouldn’t be going to the grammar school despite passing his 11 plus exams.

“They said ‘he has to learn the English ways’,” said Norwell. “It was just a way of saying ‘we can’t have black boys going to the grammar school’.”

“That was racism too,” he said. “But I didn’t know real racism until I joined the police force.”

‘Camden Town turned me into a yob’

Norwell – born Norwell Gumbs – was always told father Everard ‘Ebby’ Gumbs had died when he was three.

But he learned later he’d fled to America, remarried and had several more kids.

A couple years later his mum moved to England – with the intention of bringing her son over once she had enough money.

In the meantime, he was raised by his strict grandparents.

“My grandfather was a sergeant in the local police, he had a black belt he soaked in urine to stiffen the leather and he beat me with it whenever I miss behaved,” said Norwell.

“It was never just a smack, it was a beating.”

Norwell on the beat at Covent Garden Market in 1972Norwell Roberts

Norwell RobertsA newspaper clipping showing Norwell helping an elderly woman who’d twisted her ankle[/caption]

Norwell RobertsHe said members of the public always treated him with respect[/caption]

By 1956, Norwell’s mum had saved up enough money, often working three jobs, and sent for him.

He recalled one day being told: “You’re going to go to England.”

Asked if he was excited or scared, he said neither, really.

“I was just a child,” he added.

“I went over with an uncle, on a ship called The Napoli.

“I can’t remember much, apart from docking at Southampton and going by train to Victoria,” he said.

“It was the first time I saw so many white faces, the only white people we saw in the West Indies we were traders.

“There was no such thing as racism in the West Indies. There was no animosity.”

Norwell’s mum had found work as a live-in companion for an elderly white lady, Edith Le Pers, when he arrived, and he recalled how her neighbours didn’t talk to her anymore.

Unlike other such staff, Georgina was able to live in the same house as her mistress, in adjoining rooms, and was treated well by her.

At St Mark’s Primary School Norwell said the other children just “wanted to touch my hair, they accepted me”.

“If I was enterprising I’d be a rich man. They were fascinated but not mean,” he joked.

However, Norwell said while walking on the street in Bromley it “wasn’t unusual for someone to say n****** as we were walking across the road”.

He remembered how their next door neighbours would pull up their flowers after planting them – and while their young daughter was his dance partner at school, she “couldn’t talk to me when she went home”.

After moving to the secondary modern on being blocked from the grammar school, Norwell was dropped on his head on the first day by sixth formers wanting to “see the colour of my blood”.

Norwell RobertsNorwell with other Met officers[/caption]

Norwell RobertsHe found out his application had been successful after seeing a newspaper headline[/caption]

Norwell RobertsNorwell received many honours during his career[/caption]

“Perish the thought, it was red – I don’t know what they must have thought.”

He still has the scar on his forehead.

“I didn’t take any notice,” he said. “To me, it was one of those things. It didn’t bother me, I didn’t think about it.”

He made lots of friends at school and remembers playing happily with the children his age in the playground.

In 1958, Norwell and his mum had moved to Camden Town – to a room in a squalid house on three floors with one shared toilet.

“We were pretty poor,” he said. “My mum remarried – he was a nasty piece of work.”

The three of them, as well as Norwell’s uncle, all slept in the same bed, topping and tailing.

He said on arriving in the UK he had a “sing song” West Indian accent but joked it was Camden Town that “turned me into a yob and I’ve never looked back since”.

He received two O-Levels in Religious Knowledge and Chemistry at Haverstock Hill Comprehensive School in Chalk Farm.

At 16 he then began work as a scientific lab technician in the Botany Department at Westfield College, University of London.

Norwell RobertsNorwell went on to have a room named after him at the police training college[/caption]

Norwell RobertsMany black officers told him if it wasn’t for him they would never have become cops[/caption]

“I was living at home, initially, but got kicked out by my mum’s partner and I moved into digs in Neasden,” Norwell explained.

“Sometimes I’d walk from Neasden to Hampstead because I couldn’t afford the fare – and sometimes I slept at the laboratory in the workshop in a cupboard.

“No one ever knew, although I’m surprised they didn’t because I was always first one there and last one out,” he said, laughing.

He went on to pass 14 subjects in his City & Guilds apprenticeship on day release at Paddington Technical College, but after getting frustrated at the lack of promotion opportunities, he applied to the Met.

“The advert said ‘London needs more policemen’. I applied and the rest is history,” he said. “They were clearly ready to take a black man, but the advert didn’t actually say that.”

It was a college friend who spotted the headline which would begin a lifelong fascination between the press and Norwell.

He was constantly pictured in the media, with his career front page news “all the way through”.

Whether he was walking the beat or halting protesters in Trafalgar Square, he was snapped and his face seen across the country and abroad.

Tabloids made cartoons out of him, and Private Eye splashed him on the front page.

He added: “I’ve got six or eight scrapbooks of my life from when I joined up, to two or three years ago.”

You had the older PCs with the most service – they were worse than the younger ones. Some of them wanted to talk to me and did but you could see they were guarded. They felt comfortable if the older ones were on leave. They wouldn’t dare, they’d get beaten up.

Norwell RobertsMet’s first black officer

He said he once asked a reporter why the media was so interested in covering every nuance of his career, and he told him: “Because you were the first.”

Norwell’s police training at Hendon Police College ran smoothly, everyone was treated equal, but on graduating one of the instructors asked where he was to be stationed.

When he told him Bow Street, he said “you’ll find things a lot different there”.

“I had no clue what he was talking about,” Norwell said. “I hardly ever went to the West End, not even in Camden Town.

“He must have known I wouldn’t be accepted. There was no racism at training school, everyone was the same.”

Describing the racism at Bow Street, he continued: “It was just awful, it never stopped, it only stopped when I moved to West End Central when I joined the CID.”

But he said in those early years of his career, apart from his pal Dave Stevens from Canada – who he was later best man for at his wedding – “it wasn’t the done thing to be friends with me”.

And even Dave couldn’t take the flack he received by association and left.

“You had the older PCs with the most service – they were worse than the younger ones,” Norwell explained.

“Some of them wanted to talk to me and did but you could see they were guarded.

“They felt comfortable if the older ones were on leave. They wouldn’t dare, they’d get beaten up.”

Asked if he can sympathise at all with them, he said: “I sympathise with them now, not then. I wish they’d been a bit more friendly.

“I think they were weak but that’s the way it was. If it came to it and if I thought it was more popular to hate me than like me, I suppose they went with the crowd.

“I don’t forgive them now, but I can understand why they did it. And I wish they hadn’t. It stayed with me.

“I used to go back to the section house and cry every day because I had no friends. It was horrible.”

Norwell was a good sportsman, particularly cricket, and he remembered one match he made five catches and some of his police colleagues were on the team.

“They spoke to me on the field but back at the station they hated me again – it was difficult for me to understand.”

“No one ever said I was picking on them because they were white and I can assure you I stopped hundreds of people during my service.”

Asked if members of the public were ever racist towards him, he said “never”, adding: “I can honestly say that.

“I think people were more intrigued. I got on well with everybody.

“Getting all this stick in the station then going out on the streets, it was like chalk and cheese.

“I loved going out because they accepted me, but in the station they didn’t accept me. That happened in those days.”

Meeting Ronnie Kray

One of the infamous villains Norwell came across was gangster Ronnie Kray at Bow Street Magistrates Court, not long before he was sent to prison for life.

“I was waiting to go into court for a case that I was dealing with, a traffic case,” he said.

“I saw this bloke there and I recognised him because he was in the papers, and it was Ronnie Kray.

“He was so smart, he had a nice suit on, he had a nice silk handkerchief, and he smelt of Brut.

“Everybody knew the smell of Brut. It was advertised by Henry Cooper. You could smell it.”

Of his exchange with Kray, Norwell said: “We just started talking. He said hello. I said ‘what you here for?’ He said ‘they got me here on a poxy traffic charge’.

“For him, an archevillain, and he’d been nicked for a traffic offence, probably speeding or something – he was offended, and that’s the last I saw of him. That’s the only thing I said to him.”

Describing the gangster, he added: “He was quite normal, he didn’t show me any animosity, he spoke to me as I’m speaking to you now.

“It (the charge) was something so trivial to him because he was thinking I kill people, I drill holes in people’s legs just for fun and they’ve got me on this. What are they thinking of?”

Who were the Kray twins Ronnie and Reggie?

RONNIE and Reggie Kray were both notorious for their ruthless East End crime empire during the 1950s and 1960s.

But who were Ronnie and Reggie Kray, what crimes did they commit and how did they die? Here’s everything you need to know.

Who were the Kray twins?

The identical twins were born within ten minutes of each other on October 24, 1933, in in Haggerston, East London.

They were born to parents Charles David Kray and Violet Annie Lee and grew up in the East End with their brother Charles.

The brothers also had a sister, named Violet who was born in 1929, however she sadly died in infancy.

Their father, also Charles, was a second-hand clothes dealer and went on the run to avoid military service.

Their maternal grandfather Jimmy “Cannonball” Lee encouraged them to take up amateur boxing, a common pastime for working class boys in the area.

Sibling rivalry spurred them on, and they reportedly never lost a match before turning professional at the age of 19.

Ronnie was considered to be the more aggressive of the two twins, constantly getting into street fights as a teenager.

From the start the pair clashed with any authority – including the Army, which like their father they did their best to avoid.

In 1952 they began their national service, but they were too wild for the military.

After assaulting the corporal in charge and several police officers, they managed to get a dishonourable discharge by throwing tantrums, dumping their latrine bucket over a sergeant and even handcuffing a guard to their prison bars.

With a criminal record their boxing careers were brought to an abrupt end, and they instead turned to a life of crime.

The twins became household names in 1964 when they were hit with an expose in the Sunday Mirror.

It insinuated that Ronnie had a sexual relationship with Lord Boothby, a Conservative politician.

No names were printed in the piece, but the twins threatened to sue the newspaper with the help of Labour Party leader Harold Wilson’s solicitor Arnold Goodman.

The Mirror backed down, sacked its editor, issued an apology and paid Boothby £40,000 in an out-of-court settlement.

Because of this other newspapers were unwilling to expose the Krays’ connection and criminal activities.

What crimes did the Kray twins commit?

In the early 50s the brothers started their gang, The Firm, which would shape their criminal activities.

Under The Firm umbrella they were involved in armed robberies, arson, protection rackets, assaults and murder over close to two decades.

Their brother Charlie provided the business brainpower behind the operations, while the twins became the public face of The Firm.

One of their first moves was to buy a run-down snooker club in Mile End, where they started several protection rackets.

Their hands-on approach to business landed them in trouble, with Ronnie convicted of GBH in the late 1950s.

In the 60s, they moved to the West End to run a gambling club, Esmerelda’s Barn, in Knightsbridge.

They were widely seen as prosperous nightclub owners and part of the Swinging London scene, even persuading a peer to join them on the board to give the club a veneer of respectability.

As owners of Esmerelda’s Barn, the twins quickly achieved celebrity status, and rubbing shoulders with the likes of lords, MPs, socialites and famous faces such as Frank Sinatra and Judy Garland.

How long did the Kray twins spend in prison?

In March 1969, both Ronnie and Reggie were sentenced to life imprisonment, with a non-parole period of 30 years for two counts of murder of Cornell – the longest sentences ever passed at the Old Bailey.

Their brother Charlie was imprisoned for ten years for his part in the murders.

Ronnie Kray was classed as a Category A prisoner and was denied almost all liberties.

He was not allowed to mix with other prisoners.

Ronnie was eventually certified insane – his paranoid schizophrenia was treated with constant medication.

In 1979 he was committed and lived the remainder of his life in Broadmoor Hospital.

Reggie Kray was imprisoned in Maidstone Prison for eight years as a Category B prisoner.

In 1997, he was transferred to the Category C Wayland Prison in Norfolk.

Reggie Kray spent a total of 33 years behind bars, before being released from prison on compassionate grounds in August 2000, at the age of 66.

He was released due to being diagnosed with inoperable bladder cancer.

Ronnie Kray spent the remainder of his life imprisoned in Broadmoor Hospital, up until his death in 1995.

How did the Kray twins get arrested?

The twins’ fortunes changed when Ronnie Kray shot and killed George Cornell, a member of rival gang the Richardsons, at the Blind Beggar pub in Whitechapel.

No one was convicted for the 1966 killing at the time.

Then, in December of that year, the Krays helped Frank Mitchell escape from Dartmoor prison.

Once out, the Krays held him at a friend’s flat in East Ham, London, but the “Mad Axeman” disappeared without trace.

Despite these public affrays, the Krays’ criminal activities continued to be faintly hidden by their celebrity status and their more legitimate businesses.

But they would not be able to escape the consequences of their next actions.

Reggie was allegedly encouraged by his brother in October 1967 to kill Jack “the Hat” McVitie, a minor member of the Kray gang who had failed to fulfil a £1,000 contract to kill Leslie Payne.

They lured him to a flat in Stoke Newington on pretence of a party.

There Reggie stabbed McVitie in the face and stomach and killed him, driving the blade into his neck.

It was then that the tide turned against the Krays, with people concerned the same fate would meet them.

In the same year Detective Leonard “Nipper” Read reopened his case against them. He had met with a “wall of silence” when investigating the Krays before.

However, by the end of 1967 Read had built up enough evidence against the Krays, and on May 8, 1968, the Krays and 15 members of their gang were arrested.

How did the Kray twins die?

Ronnie remained in Broadmoor Hospital until his death on March 17, 1995, after suffering from a heart attack at the age of 61.

Reggie was released from prison on compassionate grounds in August 2000, eight and a half weeks before his death from cancer.

Their reputation preceded them even in death, with onlookers crowding the streets to catch a glimpse of the famed gangster’s coffin as it was taken through the East End.

Were the Kray twins married?

Ronnie Kray, who identified as bisexual, said he planned on marrying a woman named Monica in the 1960s, who he had dated for nearly three years.

He was arrested before he had the chance to marry Monica – who ended up marrying Ronnie’s ex-boyfriend.

He married twice afterwards – to Elaine Mildener in 1985 at Broadmoor chapel, who he then divorced four years later.

Ronnie then married Kate Howard, who he also divorced in 1994.

His brother Reggie, first married Frances Shea in 1965.

However, just two years later, his wife committed suicide.

In 1997, Reggie married once again, this time to Roberta Jones who he met while still in prison.

Did the Kray twins have any children?

Neither Ronnie or Reggie had any children.

However, Sandra Ireson, a 64-year-old mother and grandmother, claims she is the daughter from a brief romance between Reggie and cabaret dancer Greta Harper in 1958.

She even tried to forge a relationship with the man she claimed to be her father, however, Reggie allegedly rejected Sandra’s attempt to forge a lasting relationship in fear of upsetting his wife, Roberta.

Eventually, his treatment by the other cops had worn Norwell down and he was looking for a way out.

In 1972 he moved to the CID at West End Central as a Temporary Detective Constable and later a fully-fledged DC at Vine Street in 1974, before a brief stint as a uniformed sergeant in West Hampstead, then back to the CID as detective sergeant.

As part of the CID, his worked in drug squads, which meant occasionally going undercover, something he continued to do for more than two decades.

However, his first such assignment didn’t quite go to plan.

He was given £2,500 to buy heroin from a dealer and then arrest him.

“I lost all the money,” Norwell said. “I thought that was it, you bought the drugs and gave money and then went.

“It’s supposed to be a set up so he gets arrested during the exchange.

“I went back to the station and I was laughing and I said ‘I got it’.

“They said ‘you f***ing got what? They were annoyed. One bloke looked like he was going to shoot me. I realised I did it all wrong.

“It had a good ending, we got the money back and they arrested him later. It never happened again.”

Norwell’s undercover work saw him sent away at short notice all over the country, while working out of West End Central, Kentish Town, Ealing, Golders Green and other stations.

But he remains largely tight-lipped about that side of his career.

“I never talk about it but it might have been drugs, or all sorts, kidnapping, any job that necessitates undercover expertise to effect an arrest.

“I enjoyed it because it’s something I could do, I enjoyed thinking on my feet. I’m very guarded about talking about it now.”

It often meant him getting dressed in elaborate disguises. “I maybe had my hair in cornrows, plated, or I’d wearing a syrup (a wig),” Norwell described.

“Sometimes it was earrings, jewellery – I looked like a million dollars. I could walk past you on the street and you wouldn’t recognise me.”

He continued: “If the job came off, and invariably it did, I was very pleased. I’d leave work, come home, get suited up. My wife didn’t know what I was doing. I went back and came back when I came back.”

Norwell and his second wife Wendy moved to Harrow in the 1970s and still remain there.

He retired from the police in 1997 and now has a room named after him at Hendon Police College.

He also received police commendations on three occasions, with Met Police Commissioner Sir Robert Mark praising his contribution towards better relations between the white and black communities.

In 1995, Norwell was awarded the Queen‘s Police Medal for distinguished service – and was presented with the medal at Buckingham Palace the following year by the then-Prince Charles.

In 2016 Hub magazine awarded him the highest category of the Creativity, Legend Award.

Norwell said other black officers told him they’d only joined the force because of him.

“I certainly paved the way for others to join,” he said.

“I don’t want to sound big headed but I think if I hadn’t made it no one else would’ve done. I really believe that.”

Norwell released an autobiography called I am Norwell Roberts in 2022 and is Revelation Films is currently seeking backing to make a documentary about his life.

Published: [#item_custom_pubDate]