DEEP into the Bolivian salt flats lies an eerie graveyard of abandoned train carriages and engines.

More than 100 steam locomotives and rail cars have been left to rust for 80 years in the “Cemetrio de trenes” – the cemetery of trains.

Haunting footage shows a graveyard of abandoned trains left to rust in BoliviaRex Features

Because the trains are not protected, many have been coated in graffitiRex Features

Over 100 old trains lie along the salt flat by the city of UyuniRex Features

The trains have been surrendering to the salt for over 80 yearsRex Features

The haunting site makes up one of the world’s largest antique train cemeteries and lies on top of a desert plain of salt that stretches over 10,000 square kilometres.

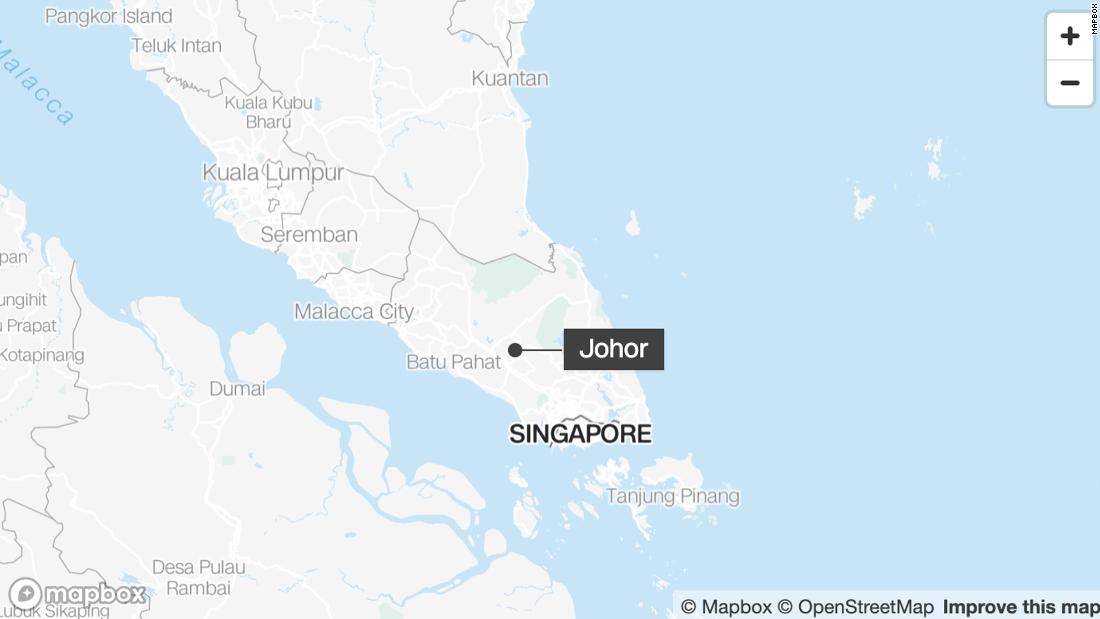

It sits three kilometres from the southwest city of Uyuni and lies 4,000ft above sea level.

Dozens of steam trains litter the landscape, many on their sides or torn apart and spread across the flats by weather or those who trekked to the site for scrap metal decades ago.

It is even believed that among the ruins is the first train that ever entered Bolivia.

The cemetery has formed an unofficial museum for tourists all over the world who travel across the barren land to see the strange graveyard for themselves.

Bolivia’s train network was built in the 19th century thanks to the British.

Engineers from the UK were invited over to help build the railway lines and the vast majority of trains were imported from Britain.

Uyuni became the rail network’s hub as the city sat at the intersection of four train lines connecting Chile, Bolivia and Argentina together.

At the end of the 19th century, the salt city was booming as the trains transported materials from high in the Andes Mountains down into the ports.

But all this ground to a screeching halt in the 1940s, when the mining industry collapsed.

The trains – no longer needed – were abandoned.

In the three-quarters of a century since, the salt flats have been working hard to erode and rust the locomotives.

Photographer Chris Staring was amazed by the sprawling and spooky graveyard in the centre of nothing but salt.

He said: “Most of the 19th century steam locomotives were imported from Britain so only designed and built for the British climate.

“Although built to withstand harsh weather conditions, the locomotives proved to be no match for the challenging conditions that they found themselves in while chugging their way through the high altitudes, thin air, corrosive salty winds and extreme temperatures in Bolivia and Chile.”

As the popularity of the site has increased, so has the colourful graffiti that adorns the blackened shells of the steamers.

Intrepid explorers can climb aboard and go back in history as they enter the carriages and driver compartments and read hand-etched messages from visitors from decades ago.

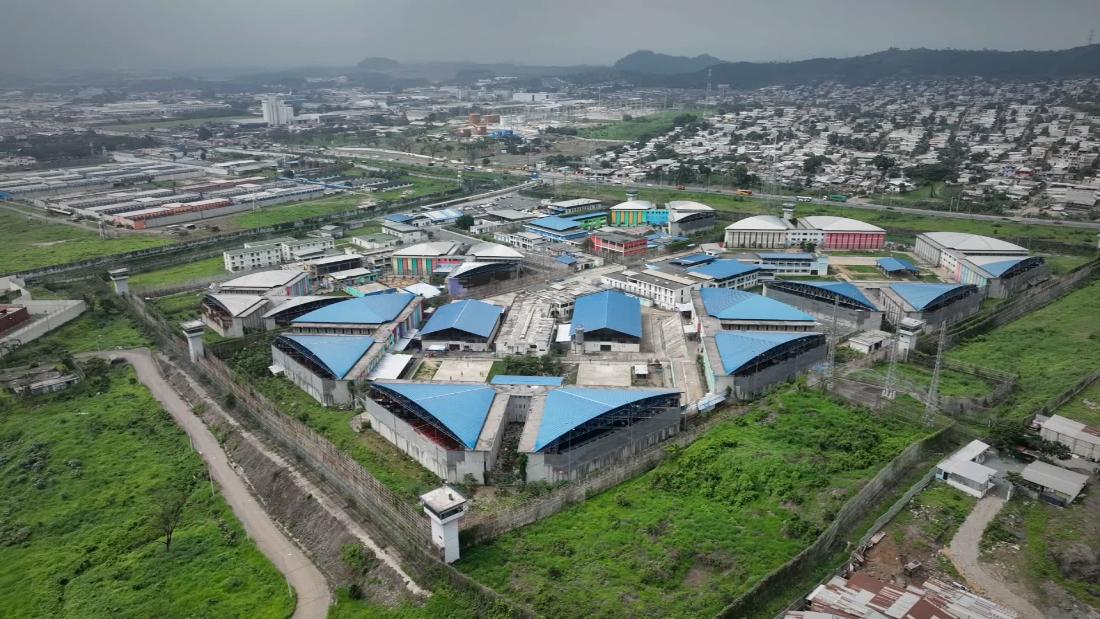

Elsewhere, under the shadow of Russia’s Ural mountains is a rusting, eerie site of a graveyard of trains built in preparation for World War 3.

The steel skeletons of dozens of steam locomotives betray a time when the spectre of the mushroom cloud loomed dangerously near.

During the Soviet era it served as a nuclear war base – ready and waiting to whisk Russians to safety if all other transportation failed or was destroyed.

Time progressed, the Iron Curtain lifted, diesel trains took over and the threat of nuclear war waned – leaving a cemetery on rusty tracks.

Among the ruins is thought to be Bolivia’s first ever trainRex Features

The British helped to develop the railway system in Bolivia in the 19th centuryRex Features

The Bolivian train system collapsed as the mining industry disappearedRex Features

Now, the ruins of the steam trains litter the barren landRex Features

The site has become a hotspot for adventurous touristsRex Features

The salt flats of Uyuni has an estimated 10 billion tonnes of saltRex Features Published: [#item_custom_pubDate]