TENDING the bar of her father’s North London pub in the early 1970s, Susan Woodthorpe was used to jokey banter with regulars.

Aged 19 and also working as a receptionist in the West End, she often stepped in during busy shifts to help pour pints and share jests with punters.

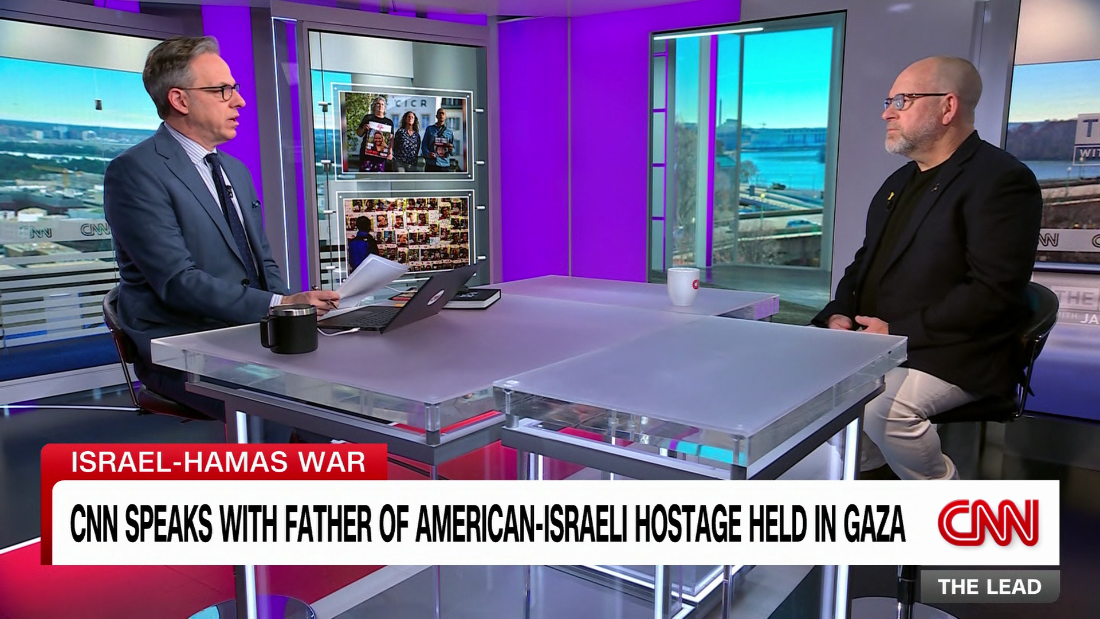

Shutterstock EditorialKGB super spy Oleg Lyalin, pictured partying in London in 1969, was regularly seen at late-night bashes and had multiple girlfriends on the go[/caption]

AlamySusan Woodthorpe struck up a friendship with Oleg Lyalin in the early 1970s[/caption]

Louis WoodSusan, now 74, met him through her work at Razno, a Russian company that set up deals for British clothing and textiles[/caption]

But one night at the boozer she shared even more with the Tottenham locals propping up the bar — unknowingly introducing them to a Soviet spy.

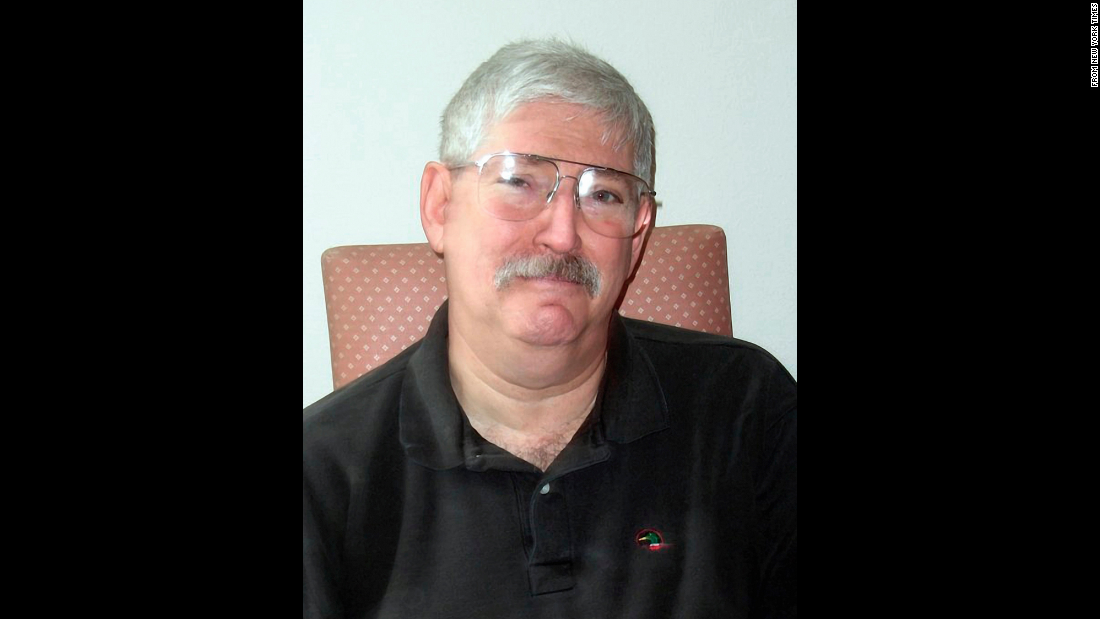

The landlord’s daughter had struck up a friendship with Oleg Lyalin, a man who would turn out to be one of the Cold War’s most important agents.

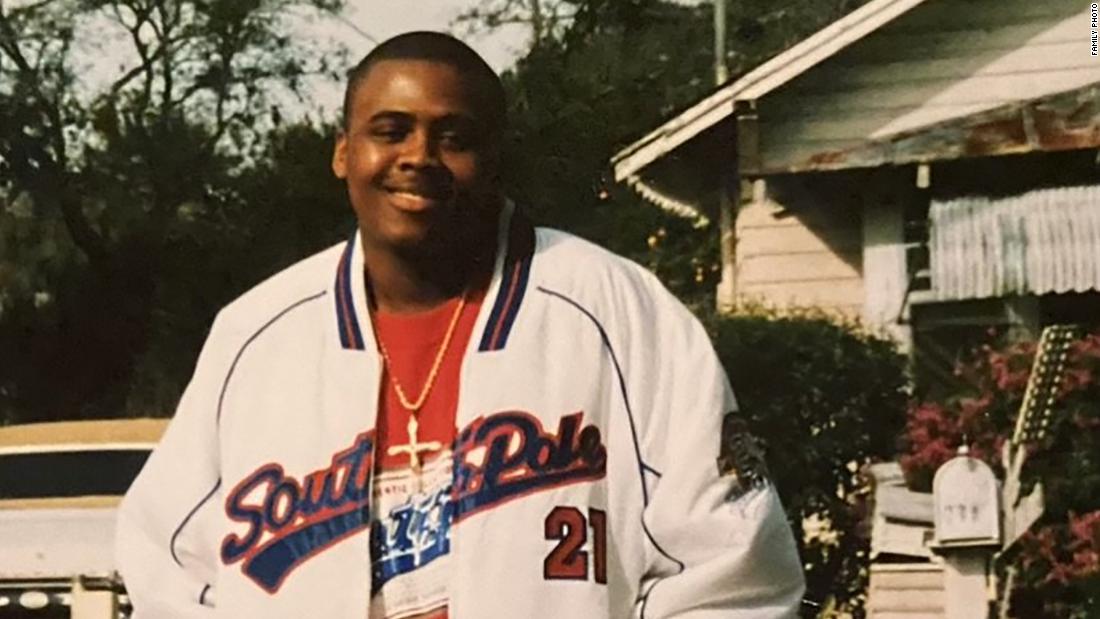

Susan, now 74, met him through her work at Razno, a Russian company that set up deals for British clothing and textiles to be sold east of the Iron Curtain.

Lyalin, then 32, was working as an official with the Soviet trade delegation and he would often appear at her office in London’s West End to discuss contracts with the company’s bosses.

Speaking impeccable English and always dressed in well-tailored high-end suits, Lyalin was leading a shady double life.

But far from keeping a low profile as an undercover KGB agent, he was regularly seen downing glasses of vodka at late-night parties and had multiple girlfriends on the go.

“He was like a whirlwind, really,” Susan tells The Sun. “He used to bring me bottles of vodka, and caviar and cream-cheese sandwiches, over from the trade delegation.

“He was a bit of a playboy. It seemed like he obviously liked to drink. He was quite flirtatious.

“I think he liked the lifestyle in this country. It suited him — the partying and the bars of the West End.

Covert attacks

“He was the kind who would always be cracking jokes — with very sort of light-hearted chat, nothing serious.

“When we did go out for a drink, it was usually an after-work drink or a lunchtime drink, just him and I.

“If I was older and more worldly-wise at that time, I probably would have taken a lot more notice. But to me, it was just a friendship.

“From time to time he’d disappear for a while and then he’d come back.”

In reality, Lyalin was operating as an undercover KGB captain for Department V, which specialised in sabotage and covert attacks.

The story of Lyalin’s secret life — and his hugely important defection to the UK — is told in full for the first time in a new book by security expert Richard Kerbaj.

Drawing on recently declassified documents — The Defector: The Untold Story Of The KGB Agent Who Saved MI5 And Changed The Cold War — paints a picture of a man who boosted the fight against Soviet spies.

In 1971, the British secret services were on their knees after a series of embarrassing high-profile scandals.

Kim Philby, one of the Cambridge Five, had fled to Russia in 1963 having been exposed as a double agent who handed over countless British secrets during the Cold War.

AlamyA police image of the KGB super spy drawn from a friend’s description[/caption]

AlamyPolice outside Russian tour operator after operation to expel 105 spies in 1971[/caption]

In 1964, art historian Anthony Blunt, who was Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, had confessed to being a Russian spy, showing that the KGB had managed to infiltrate the very heart of the British establishment.

The Sixties also saw the Profumo affair, which saw Tory war minister John Profumo forced to resign after admitting to an affair with showgirl Christine Keeler, who was also involved with a Soviet naval attache in London.

Lyalin’s decision to turn himself in to MI5 could not have come at a better time for the agency. His disappearances, as remembered by Susan, were likely trips to meet agents he was managing in the UK, or journeys back to Russia to see his wife Tamara and their young child.

Despite being married, Lyalin was juggling multiple love affairs, including one with Irina Teplyakova, his glamorous colleague at the trade mission.

But it was not until Lyalin was arrested for drink-driving in the summer of 1971 that his chaotic life-style came to a head.

Bailed by an embassy official, and with his name appearing in a brief newspaper cutting about the arrest, he was ordered back to Moscow.

But Lyalin had no intention of returning to Mother Russia and his young family. Instead, he claimed political asylum with MI5, and took his mistress Irina with him.

Equally, if not more impressive, was that Lyalin’s intelligence to MI5 ultimately forced the closure of Department V, the KGB’s assassinations and sabotage branch to which he once belonged.

While it is not known exactly why he decided to turn himself in, it is thought that his whirlwind personal life had taken a toll.

Once British intelligence had him in a safe house away from his familiar haunts in Soho, the true scale of KGB deception was laid bare.

Among the plans which he had been asked to draw up was poisoning a Scottish loch with radioactive waste in order to spread dissent around the UK and US’s nuclear submarines.

Another included identifying spots along the Yorkshire coastline where Soviet saboteurs could land while going undetected.

He also handed over the names of agents he was co-ordinating in London. One under his control had knowledge of the licence plates used to ferry round royalty, government officials and intelligence chiefs.

Another was found with devices including fake batteries and pens which were used to convey messages back to his KGB master.

Lyalin’s defection led to the expulsion of more than 100 Soviet spies at the height of the Cold War — the biggest-ever purge of Kremlin officials from any one country.

Dubbed Operation Foot, the mass expulsion crippled the Kremlin and allowed Britain to turn the tables on the KGB after a decade of embarrassing failures.

State of paranoia

Author Kerbaj told The Sun: “In 1971, Britain had 550 Soviet officials — more per capita than in any other Western nation.

“Of those, about 200 were suspected of being spies.

AlamyDubbed Operation Foot, the mass expulsion crippled the Kremlin and allowed Britain to turn the tables on the KGB[/caption]

GettyTory war minister John Profumo was forced to resign after admitting to an affair with showgirl Christine Keeler, who was also involved with a Soviet naval attache[/caption]

The Kremlin in Moscow during Cold WarAlamy

“Oleg Lyalin exposed their identities to MI5, identifying those working undeclared for the KGB, and the GRU, the Kremlin’s military intelligence agency.

“The information played a central role in helping MI5 initiate the mass expulsion of Soviet spies from Britain and ultimately forced the KGB into a state of paranoia about other potential defectors in its midst.

“Equally, if not more impressive, was that Lyalin’s intelligence to MI5 ultimately forced the closure of Department V, the KGB’s assassinations and sabotage branch to which he once belonged.”

In briefings to the papers before the announcement, the Foreign Office said that this had only been possible due to the defection of a high-level Soviet spy.

The first Susan knew about her friend’s double life was when his story was splashed over the newspapers. The morning headlines read: Super Spy Oleg and Yes, Oleg Was The Super Spy.

“I was quite shocked,” says Susan. “From what I’ve learnt since, obviously he was not the person that I knew. I think at age 19 or 20, you didn’t really think about it too much. I was too busy just sort of getting on with life.

“Looking back, when he came to Razno, he used to come to the offices and everything was done behind closed doors.

“There was one time that one of the directors had his office rifled through.”

There was also a call to her father’s pub in late 1970, which Susan now believes must have been MI5 attempting to look into her Russian friend.

Double life

She says: “When I got home, my father said, ‘You’re never going to believe this’.

“He said, ‘I’ve had MI5 or someone like that down here wanting to speak to you’.

Shutterstock EditorialThe first Susan knew about her friend’s double life was when his story was splashed over the newspapers[/caption]

suppliedThe Defector: The Untold Story Of The KGB Agent Who Saved MI5 And Changed The Cold War by Richard Kerbaj (Bonnier, £25) is out on September 4[/caption]

“They were more or less asking his permission to make contact with me. I was given a number and a name. I can’t remember the name exactly but it was something like John Smith. I was at work at Razno, and I’d got this number in my pocket.

“So I went around to the pub — just around the corner from the offices — where they had a phone box in the basement.

“I made this phone call and spoke to somebody from MI5 or it could have been MI6.

“They more or less asked me if I could be approached if I was needed to help them out.”

Susan quit her job at Razno before she had got the chance to take that any further.

She says of Oleg now: “I have often wondered over the years about where he was. Was he alive still? Or in this country? But I never heard anything.” The British service gave Oleg and Irina new identities and they then disappeared into new lives somewhere in the north of England.

Lyalin died aged 57, in 1995, after a long illness.

He had in 1972 been sentenced to death in the Soviet Union, in his absence, for his betrayal.

Locals convinced Susan to give a TV interview after news broke of Lyalin’s identity, in which she remembered him as a “charmer” who did not take life too seriously.

And it was not long before the pub’s regulars had a new nickname for their favourite boozer: The Spies.

The Defector: The Untold Story Of The KGB Agent Who Saved MI5 And Changed The Cold War by Richard Kerbaj (Bonnier, £25) is out on September 4.

Published: [#item_custom_pubDate]