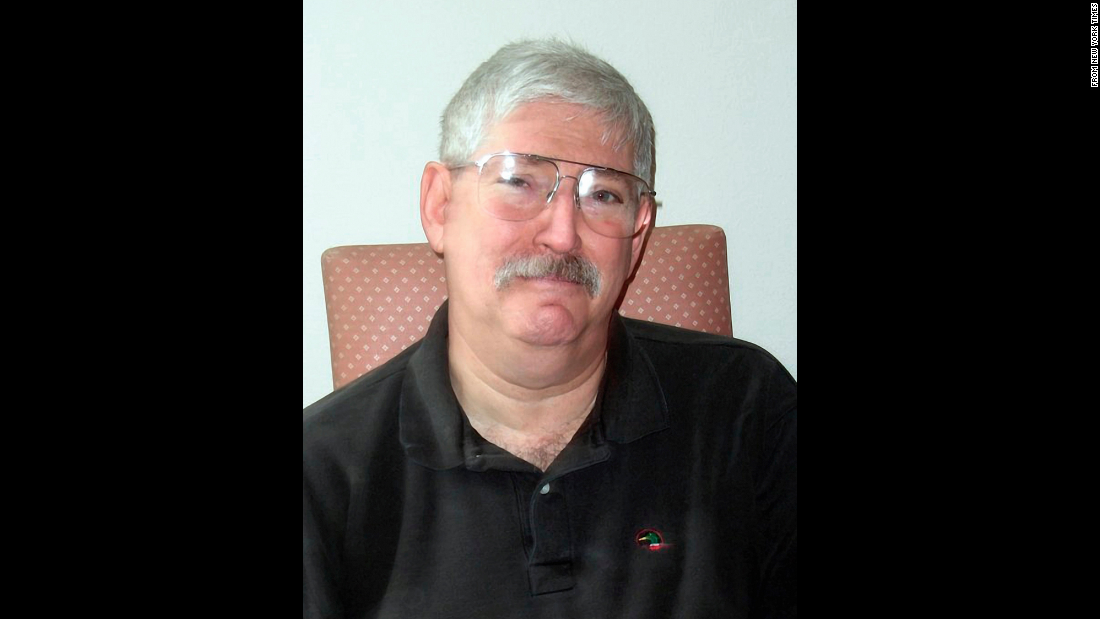

HERBERT SUTCLIFFE was one of the all-time greats of English cricket, a master batsman during the inter-war years who raised the standing of professionals by his achievements.

So you would have thought that in his old age he had earned the right to indulge in a few of his favourite pleasures, including his fondness for gin.

Why should people in the twilight of their lives be deprived of something that has given so much joy to mankind since the dawn of time?Shutterstock

But when he had to go into a Yorkshire nursing home due to his infirmity, the staff instituted a ban on this habit.

As Don Mosey, the cricket commentator and Sutfcliffe’s friend, recalled: “It became necessary to smuggle the stuff past a Praetorian guard of nurses, sisters and matrons, who became expert at spotting the gin-smugglers.”

On one occasion, Mosey tried to sneak in a bottle of Gordon’s hidden in a holdall covered with a tape recorder.

“The staff headed me off before I could start up the stairs to his room, searched out the gin and confiscated it,” he said.

Mosey felt sheepish as he entered Sutcliffe’s room. “You’ve let those bloody awful creatures take it, haven’t you?”, Sutcliffe said angrily, sitting upright in his wheelchair.

Cruelty dressed up

The great cricketer was fully justified in feeling aggrieved.

What right did the management have to deprive him of a creature comfort he adored, especially when the physical horizons of his life were now so severely restricted by his disability?

They said that gin was “not good for him”.

But from what were they trying to protect him, given that he was already in his eighties?

EmpicsHerbert Sutcliffe was one of the all-time greats of English cricket, but that didn’t stop care home staff banning him from drinking his favourite tipple of gin[/caption]

There was nothing compassionate about the prohibition on alcohol. On the contrary, it was cruelty dressed up as concern for safety.

Sutcliffe died in 1978 but the nanny-state attitude still prevails in too many of our care homes.

That reality was highlighted yesterday in the publication of a new study carried out by the heath watchdog the Care Quality Commission in partnership with the University of Bedfordshire.

It found that a quarter of homes took “a risk averse” approach and placed “disproportionate restrictions on residents’ drinking”. In the name of safety, these unlucky clients are being treated as too irresponsible to make their own decisions.

As the report puts it, some staff have become “paternalistic” and were “wrapping people in cotton wool” by not allowing them to drink.

This is not protection, it is punishment.

Why should people in the twilight of their lives be deprived of something that has given so much joy to mankind since the dawn of time?

In the words of Hollywood comedian W.C. Fields, “A woman drove me to drink and I never had the chance to thank her.”

Particularly at Christmas, alcohol is the vital lubricant for the festive season. Those whose condition requires them to be looked after should not be isolated further by arbitrary blanket bans.

As Dr Sarah Wadd, one of the report’s authors, sensibly put it: “People living in care homes should be supported to have as much choice and control over their lives as possible.

“It is important to remember that just as health has a value, so too does pleasure.”

Her report confirms the findings of other recent surveys, like one carried out in 2020, which revealed that a fifth of care staff say that residents are banned from drinking in their homes.

This draconian outlook stems from a number of factors.

One is the infantilising, patronising spirit that can arise from the very nature of care work where residents, because of their frailty or vulnerability, come to be seen as incapable of taking responsibility.

Another is the modern obsession with the avoidance of danger, partly in response to the compensation culture and partly due to the box-ticking, risk assessment-making health and safety brigade.

It is viewpoint encapsulated in the comment of the former Chief Medical Officer Dame Sally Davies, who once told a Commons Committee that people should “do as I do when I reach for my glass of wine, and think: Do I want a glass of wine or do I want to raise my risk of cancer?”.

The same ultra-cautious spirit shone through a ridiculous experiment in Lancashire, where care home residents were asked to sign legal disclaimers if they wanted to eat soft boiled eggs.

At a care home in Surrey, one former RAF crewman was outraged when runny eggs were banned at breakfast on health grounds.

During the war, he told the home manager, he had faced far greater dangers than a soft-boiled egg.

Moral superiority

When I first started working for this paper in the mid-Nineties, one of the earliest stories I handled was about a report from the Health Education Authority, which had voiced its concern about the “under-recognition of drinking among the elderly”.

To the horror of researchers at the HEA, some older people in their survey “talked openly about how much they enjoyed drinking alcohol”. Just as regrettably, certain doctors “collude with this way of thinking” through their belief that “a little alcohol won’t hurt”.

Moral superiority, authoritarianism and fear about drink have existed in most Western societies, inspiring the temperance movement here in the 19th century and prohibition in 1920s America.

The modern alcohol banners are the same type of puritan.

The great US journalist HL Mencken wrote puritanism is the “haunting fear that someone, somewhere may be happy”.

The public health zealots should not be allowed to deprive older people of their last moments of fun.

Those who spend their final days in care homes are often those who have contributed most to our society.

A regular, delicious tipple is the least we owe them.

GettyIn the words of Hollywood comedian W.C. Fields, ‘A woman drove me to drink and I never had the chance to thank her’[/caption] Published: [#item_custom_pubDate]