CHANCELLOR Rachel Reeves is walking Britain into an alligator pit of maxed-out borrowing, higher taxes and stuttering growth.

But there is something else now snapping at her high-tax heels — the soaring number of people on out-of-work benefits.

GettyThere are now over one million more people on Universal Credit since Labour took office[/caption]

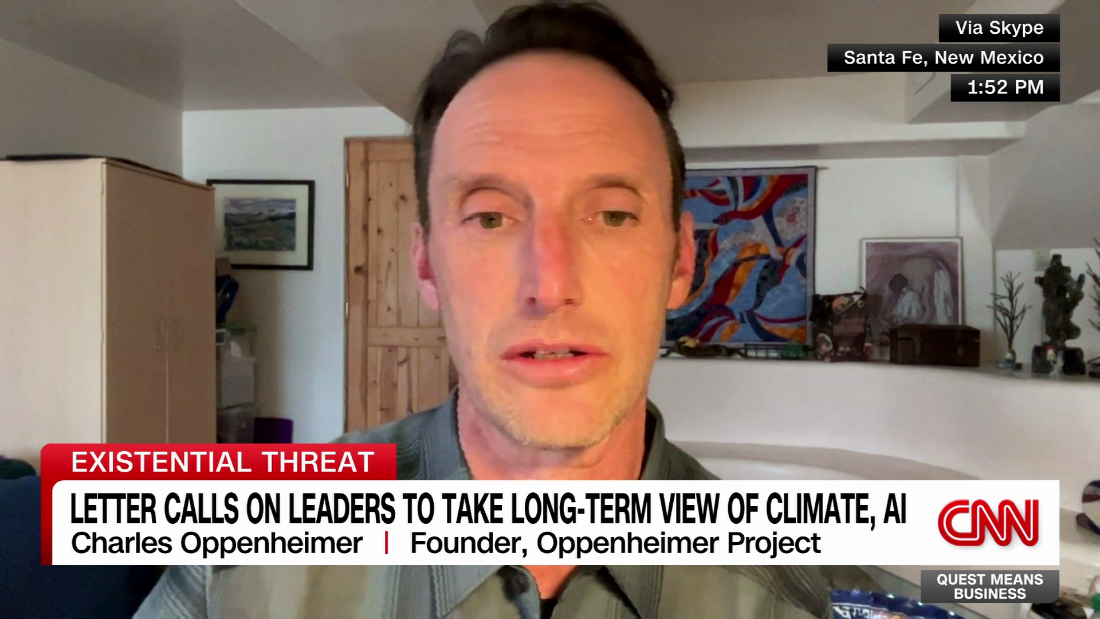

GettyRachel Reeves is walking Britain into an alligator pit of maxed-out borrowing[/caption]

New figures this week showed that, since Labour took office, there are now over one million MORE people on Universal Credit — that’s the size of the population of Birmingham.

By 2030, the cost of sickness benefits alone will reach £100billion — more than the entire defence budget.

Thousands of people are being written off, their potential wasted. And with hardworking families set to be clobbered by further tax hikes this autumn, Sun readers will rightly ask, “What is going on?”.

As the Work and Pensions Secretary responsible for getting Britain to record employment levels in the 2010s, I know that unless they get welfare under control, taxpayers face a tax bomb overwhelming them this autumn.

‘Work instilled pride’

To recap, before Covid, my reforms put a hard cap on unemployment benefits and combined them so that jobseekers were always better off in work.

We brought in tough new rules and a contract for claimants to sign in return for their benefits, ensuring they looked for a job and took one, with a work coach’s help.

With this approach, we got 1,600 people into jobs every single day.

Workless households fell to their lowest level ever. And half a million more children grew up seeing a parent going out to earn a living — changing their life chances forever.

I took the view that work was more than just a paycheck but, importantly, it instilled purpose and pride in your life.

Sadly, in 2020, Covid lockdowns saw benefit assessments massively relaxed and sanctions suspended. Meetings were shunted online and never held in person again — a terrible error.

Meanwhile, perverse incentives crept into the system, allowing more and more people on to (significantly more generous) sickness benefits. Since then, long-term sickness claims have exploded, rising to almost 3,000 per day.

The number of people receiving Personal Independent Payments for anxiety and depression has trebled. Meanwhile, the number of households where no one has ever worked has also risen.

Analysis by the think tank I set up, The Centre For Social Justice, found that once all benefits are totted up, you can now receive £2,500 a year more on benefits than someone would receive on the national living wage after tax.

In other cases, such as a single parent claiming for anxiety and a child with ADHD, total annual support can reach nearly £37,000 — over £14,000 more than the same person would earn through wages alone.

Our post-Covid ballooning welfare bill has to be tackled urgently

Iain Duncan Smith

A system designed to protect disabled people in genuine need has morphed into one that too often disincentivises work, traps people in long-term dependency and leaves them without meaningful support to recover.

This isn’t the whole story. There are, at the extremes, young and old at both edges of the welfare crisis.

With almost one million youngsters not in education, employment or training (NEET), the epidemic of school absences could yet see an extra 180,000 pupils join their ranks.

And we are leaking talent and experience out of the workforce at an alarming rate, with record numbers of people aged 50-64 on out-of-work benefits.

The government must start by addressing the surge in claims since the pandemic, particularly for mental health. But the government has got off to a bad start.

The Treasury’s push to get quick savings in time for the spring resulted in a rebellion by Labour backbenchers and a U-turn costing £3billion.

Yet this ballooning welfare bill has to be tackled, and the CSJ has shown there is a way.

First, tighten eligibility for benefits to people with more severe mental health conditions while reinvesting the savings in the support we know genuinely helps people to recover. In-person assessments and benefit sanctions for those failing to seek work must be restored in full.

The CSJ shows that this would save over £7billion, a large portion of which should be spent radically expanding NHS therapy and back-to-work help.

Second, we need to stop people falling out of work in the first place.

‘Young hardest hit’

Medicalising the ups and downs of life has resulted in 93 per cent of consultations with a GP ending up with someone signed off altogether rather than keeping them in their job.

A proper work and health system should take “sick notes” provision off GPs, allowing them to devote their time to people, particularly those aged 50–64, needing workplace adjustments.

Third, I worry more each day about Britain’s young people. The government’s National Insurance rises have put up wage costs, making businesses less likely to give them a chance.

Getting people back to work is critical for us all

Young people are the hardest hit by the £25billion jobs tax.

Instead, the Chancellor should cut taxes on jobs and introduce a new tax credit for businesses hiring young British NEETS, a CSJ proposal backed by many employers who have called for this.

Our post-Covid ballooning welfare bill has to be tackled urgently.

But as employment numbers fall in response to higher taxes, Reeves has made it harder to do this.

Getting people back to work is critical for us all.

Published: [#item_custom_pubDate]