NEVER judge a book by its cover is a pretty good rubric, especially if you live on a desert island with a dozen washed-up volumes — you’ve got the time to leaf through each one and decide on its merits.

As is Martin Luther King Jr’s dictum about judging people by the content of their character.

ReutersAxel Rudakubana admitted murdering three girls in the Southport rampage[/caption]

PAElsie Dot was stabbed to death at a dance class[/caption]

PABebe King, 6, was among the youngsters stabbed to death[/caption]

PAAlice Dasilva Aguiar was also left dead in the rampage[/caption]

But whether we’re talking books or people, in real life we need to make quick judgments, and anyway, we can afford the odd mistake.

Paperbacks don’t break the bank, and can be put aside if the first few pages don’t please.

When a friendship fails to bloom, nobody needs to return the call.

But for those in the business of assessing terror suspects the cost of a bad choice could be monumental; and those costs are usually paid by people who have no part in judging who is to be trusted and who is not.

Last summer, three little girls paid a price for someone else’s failure to discriminate between the merely dotty and the truly dangerous.

Another 23 children and their teacher will bear the physical and emotional scars of that savage attack for the rest of their lives.

That is why the inquiry into the massacre at Southport is so important.

It needs to do its work thoroughly and quickly.

The Chancellor was right to tell me that “no stone should be left unturned”.

But the inquiry must not allow itself to be deflected into ass-covering cul-de-sacs.

Not even the killer’s defence team is making the case that he was mentally ill.

The attempt to lay blame at the door of online suppliers of knives is a distraction; every kitchen in Britain could have supplied the murder weapons.

And it would help if ministers grew up, took responsibility and stopped hiding behind what they tell us is the law, but actually is not.

‘MISSED THE SIGNALS’

Both the independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, Jonathan Hall KC, and his predecessor, Lord Carlile of Berriew, told The Times in September that the Government could and should have spoken more openly about the killer’s background.

“One of the problems and the consequences of the Southport attack was that there was an information gap, a vacuum, which was filled with false speculation,” said Hall.

“I personally think more information could have been put out safely without comprising potential criminal proceedings.”

The inquiry should first dismiss the idea that we are facing a new phenomenon, the non-ideological, “lone wolf” terrorist.

The Prevent programme has recognised this type of terrorism since 2017.

In June 2019, the Home Office and counterterror police sent out guidance to remind schools, colleges and police that Prevent referrals should include what insiders called the “mad and the bad”.

Second, any thorough investigation needs to ask whether those who missed the signals did so because they did not want to ask difficult questions about the killer’s racial background; what the Prime Minister coyly calls “cultural sensitivities”.

We have been here before.

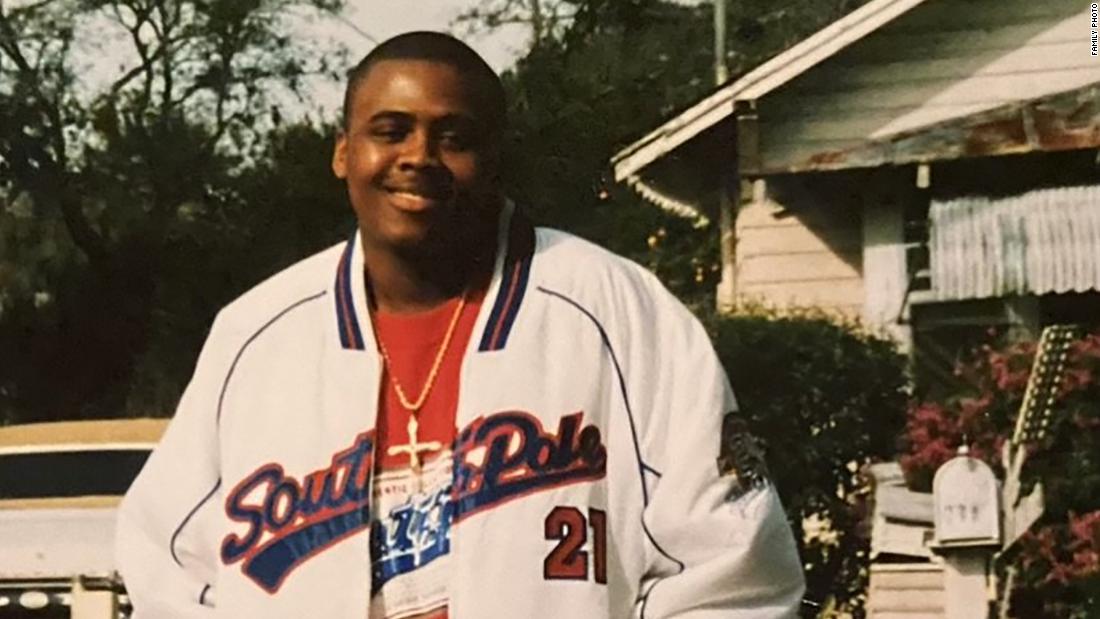

In 2007, I was asked by Gordon Brown to investigate a spate of gruesome stabbings in the capital involving teenage and pre-teenage boys, mostly black.

I wasn’t a Brown favourite; but I suspect that no one else wanted to touch the issue because of the race factor.

Admissions to A&E departments in London had doubled to nearly a thousand.

The killing of Damilola Taylor had made international news; the hunting down of Kodjo Yenga in a shopping centre by a gang, the oldest of whom was 16, did not make much news but was more typical than Damilola’s death.

What most startled me was the preponderance of children born into families who had fled African war zones, mostly Somalia, Ethiopia and Congo.

I wrote privately to Brown recommending a programme of psychotherapeutic interventions because “many of the young men have grown up inured to a level of violence unthinkable to most British people — boys who have seen family members maimed, raped or murdered in front of their eyes”.

Axel Rudakubana was born here; it is not obvious why he should have inherited any trauma.

But something is going wrong and some minority communities are at the heart of it.

It is estimated by lawyers that 75 per cent of those standing trial for homicide at the Old Bailey every year are from a black background, many from war-torn territories.

We cannot and should not ignore the evidence before our eyes.

Finally, the right questions need to be asked about Prevent.

Until 2019, referrals by police, teachers, social workers and other professionals on the grounds of potential Islamist threat remained steady at about 3,500 each year, about 45 per cent of the total.

Referrals of right-wing suspects, always much lower, were steady at around a third of that number.

But in 2019, the number of Islamist cases suddenly fell off a cliff, down to 1,500.

‘NO IDEOLOGY, NO RISK’

No such change affected right-wing referrals.

But what did change was the introduction of a new category of Prevent cases: “vulnerability but no ideology or counterterrorism risk”.

It is very likely that this is the category into which Rudakubana would have fallen.

As steeply as the Islamist category had fallen, the “no-ideology” category shot up to reach 2,500 last year.

In short, two thirds of the cases that might previously have been categorised as “Islamist” were, in effect, reassigned to a “no ideology, no risk” category.

Why? There is, in my view, only one likely explanation.

Towards the end of 2018, a group of MPs, led by the current Health Secretary, Wes Streeting, published a report calling for an expansive definition of the term Islamophobia.

Many, including myself, in a report for the Policy Exchange think tank, warned that its loose terms (“a type of racism . . . that targets expressions of Muslimness”) would lead to the chilling of speech, particularly in public services.

Police leaders told Parliament they feared the definition would hamper both Prevent and counterterrorism.

They were acutely aware that after the Manchester Arena atrocity in 2017, the security guard who spotted the bomber’s massive backpack admitted he had failed to intervene for fear of appearing to be racist.

The definition was never endorsed by government but it was adopted by dozens of local authorities and other bodies, including the Labour Party itself.

It is not hard to imagine many officials opting for the easy life and ticking the “no ideology” box.

In cases such as Rudakubana’s, “no ideology” evidently came to mean “no action”.

Those chickens that seemed to be abstract “culture wars” may be coming home to roost, and they are covered in the blood of children.

This article first appeared in The Times

Published: [#item_custom_pubDate]